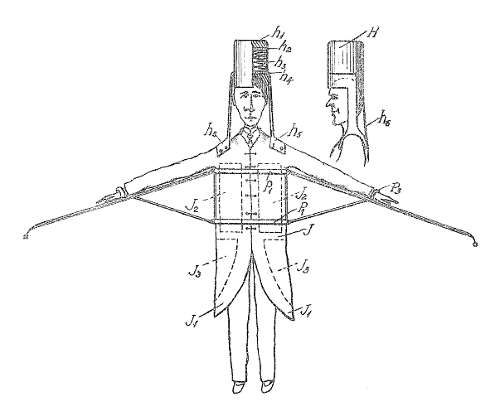

Hungarian inventor Michael Kispéter offered this safety suit for air travelers in 1915 — a jacket lined with inflatable cushions, a torso-mounted parachute, and a helmet fitted with a spring:

A person falling from the air, equipped with my life saving apparatus, will first open the parachute … Should the person fall into water, the air-cushions will keep him or her afloat, and should the respective person fall on land and the parachute not assure a descent smooth enough to prevent a violent impact with same, the impact will considerably be reduced also by the air cushions. Should the person fall head foremost the sides of the helmet will break on contact with the soil and the resilient means contained in the helmet will mitigate the concussion.

I can’t tell whether Kispéter ever tested his contraption, but he’s not the only inventor who was thinking along these lines.