In Montana Salish, a Native American language of the Pacific Northwest, the word for automobile is p’ip’uyshn — literally, “it has wrinkled feet.”

The Nez Perce word for telephone, cewcew’in’es, means “a thing for whispering.”

In Montana Salish, a Native American language of the Pacific Northwest, the word for automobile is p’ip’uyshn — literally, “it has wrinkled feet.”

The Nez Perce word for telephone, cewcew’in’es, means “a thing for whispering.”

In 1878 Queen Victoria invited to lunch an elderly naval officer who was hard of hearing. For a time the two discussed the recent sinking of the naval training ship Eurydice. Then, to turn to a lighter subject, the queen inquired after the admiral’s sister.

“Well, ma’am,” he replied, “I am going to have her turned over and take a good look at her bottom and have it well scraped.”

“The effect of his answer was stupendous,” wrote the queen’s grandson, Kaiser Wilhelm II. “My grandmother put down her knife and fork, hid her face in her handkerchief and shook and heaved with laughter till the tears rolled down her face.”

Catherine de Medicis (queen of France) made a vow that if some concerns which she had undertaken terminated successfully, she would send a pilgrim to Jerusalem, who would walk there, and every three steps he advanced, he should go one back at every third step. It was doubtful whether there could be found a man sufficiently strong to go on foot, and of sufficient patience to go back one step at every third. A citizen of Verberie offered himself, and promised to accomplish the queen’s vow most scrupulously. The queen accepted his offer, and promised him an adequate recompence. He fulfilled his engagement with the greatest exactness, of which the queen was well assured by constant enquiries.

— William Granger, The New Wonderful Museum, and Extraordinary Magazine, 1804

The sign for brother in Taiwanese Sign Language is an extended middle finger.

In 1967 University of Chicago linguist Jim McCawley proposed that fuck, when used as an epithet, as in Fuck you, is not a verb, because it accepts none of the adjuncts of a normal sentence:

Also, Fuck you “has neither declarative nor interrogative nor imperative meaning; one can neither deny nor answer nor comply with such an utterance.”

What is it, then? McCawley proposed “quasi-verb,” a new category that can be followed by a noun phrase.

The full paper is here; the journal Language credits it with being the first satirical linguistics paper.

“Madam, it is the hardest thing in the world to be in love, and yet attend to business. A gentleman asked me this morning, ‘What news from Lisbon?’ and I answered, ‘She is exquisitely handsome.'” — Richard Steele

An optical illusion or mirage was seen by three or four farmers a few miles from this city a few days since, the appearance of which no one is able philosophically to account for. The facts are these: A gentleman, while plowing in a field with several others, about 7 P.M., happened to glance toward the sky, which was cloudless, and saw apparently, about half a mile off in a westerly direction, an opaque substance, resembling a white horse, with head, neck, limbs, and tail clearly defined, swimming in the clear atmosphere. It appeared to be moving its limbs as if engaged in swimming, moving its head from side to side, always ascending at an angle of about 45°. He rubbed his eyes to convince himself that he was not dreaming, and looked again; but there it still was, still apparently swimming and ascending in ether. He called to the men, about 100 yards off, and told them to look up, and tell him what they saw. They declared they saw a white horse swimming in the sky, and were badly frightened. Our informant, neither superstitious nor nervous, sat down and watched the phantasm, (if we may so call it,) until is disappeared in space, always going in the same direction, and moving in the same manner. No one can account for the mirage, or illusion, except upon the uneven state of the atmosphere. Illusions of a different appearance have been seen at different times, in the same vicinity, frightening the superstitious and laughed at by the skeptical.

— Telegram from Parkersburg, W.Va., to the Cincinnati Commercial, reprinted in the New York Times, July 8, 1878

All persons of higher °

Are proud of a long pe°

And even the masses

Of inferior classes

Unless they are misle°.

— Cyril Bibby

In 1962, Seattle’s Swedish Hospital began offering kidney dialysis to outpatients. Because the program could accept only 17 patients, it turned to an “admissions and policy committee” made up of largely of laypeople: a minister, a lawyer, a housewife, a labor leader, a state government official, a banker, and a surgeon.

In order to narrow the field of applicants, the committee considered whether a candidate was employed, had dependent children, was educated, had a history of achievements, and had the potential to help others. In its deliberations it would also evaluate the candidate’s personality, his personal merits, and the strengths and weaknesses of his family. “The preferred candidate was a person who had demonstrated achievement through hard work and success at his job,” wrote sociologists Renée Fox and Judith Swazey, “who went to church, joined groups, and was actively involved in community affairs.”

As word spread, observers raised questions about the ethics of the program. In spring 1963, the Seattle Times presented a picture of nine dialysis patients on its cover, with the heading “Will These People Have to Die?” A committee member protested, “We are picking guinea pigs for experimental purposes, not denying life to others.” But in 1972 Congress established federal support for anyone needing dialysis, partly in response to these concerns, and today the “Seattle experience” is remembered as a formative case in bioethics.

When entomologist Paul Marsh was given the chance to name two wasp species in the genus Heerz, he called them Heerz tooya and Heerz lukenatcha.

The International Commission on Zoological Nomenclature insists that “A zoologist should not propose a name that, when spoken, suggests a bizarre, comical, or otherwise objectionable meaning.” But a few get through. Examples:

Three mythicomyiid flies are named Pieza kake, Pieza pi, and Pieza deresistans.

In 1912 the Zoological Society of London criticized entomologist George Kirkaldy for giving a series of hemipterans the generic names Polychisme, Elachisme, Marichisme, Dolichisme, Florichisme, and Ochisme (“Polly kiss me,” “Ella kiss me,” “Mary kiss me,” “Dolly kiss me,” “Flora kiss me,” “Oh, kiss me!”). In the same spirit, in 2002 a hopeful Neal Evenhuis named a fossil mythicomyiid Carmenelectra shechisme. “The offer’s still good,” he told the Chicago Tribune in 2008. “I’ll be willing to meet her.”

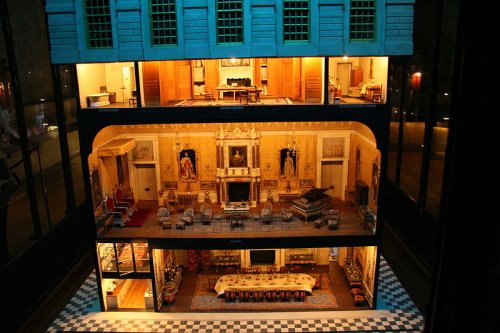

At 503 words, this is the shortest Sherlock Holmes story that Arthur Conan Doyle ever wrote. It was inscribed in a book 1.5″ high and contributed to the library of a dollhouse built for Queen Mary, the wife of George V:

How Watson Learned the Trick

Watson had been watching his companion intently ever since he had sat down to the breakfast table. Holmes happened to look up and catch his eye.

‘Well, Watson, what are you thinking about?’ he asked.

‘About you.’

‘Me?’

‘Yes, Holmes. I was thinking how superficial are these tricks of yours, and how wonderful it is that the public should continue to show interest in them.’

‘I quite agree,’ said Holmes. ‘In fact, I have a recollection that I have myself made a similar remark.’

‘Your methods,’ said Watson severely, ‘are really easily acquired.’

‘No doubt,’ Holmes answered with a smile. ‘Perhaps you will yourself give an example of this method of reasoning.’

‘With pleasure,’ said Watson. ‘I am able to say that you were greatly preoccupied when you got up this morning.’

‘Excellent!’ said Holmes. ‘How could you possibly know that?’

‘Because you are usually a very tidy man and yet you have forgotten to shave.’

‘Dear me! How very clever!’ said Holmes. ‘I had no idea, Watson, that you were so apt a pupil. Has your eagle eye detected anything more?’

‘Yes, Holmes. You have a client named Barlow, and you have not been successful with his case.’

‘Dear me, how could you know that?’

‘I saw the name outside his envelope. When you opened it you gave a groan and thrust it into your pocket with a frown on your face.’

‘Admirable! You are indeed observant. Any other points?’

‘I fear, Holmes, that you have taken to financial speculation.’

‘How could you tell that, Watson?’

‘You opened the paper, turned to the financial page, and gave a loud exclamation of interest.’

‘Well, that is very clever of you, Watson. Any more?’

‘Yes, Holmes, you have put on your black coat, instead of your dressing gown, which proves that your are expecting some important visitor at once.’

‘Anything more?’

‘I have no doubt that I could find other points, Holmes, but I only give you these few, in order to show you that there are other people in the world who can be as clever as you.’

‘And some not so clever,’ said Holmes. ‘I admit that they are few, but I am afraid, my dear Watson, that I must count you among them.’

‘What do you mean, Holmes?’

‘Well, my dear fellow, I fear your deductions have not been so happy as I should have wished.’

‘You mean that I was mistaken.’

‘Just a little that way, I fear. Let us take the points in their order: I did not shave because I have sent my razor to be sharpened. I put on my coat because I have, worse luck, an early meeting with my dentist. His name is Barlow, and the letter was to confirm the appointment. The cricket page is beside the financial one, and I turned to it to find if Surrey was holding its own against Kent. But go on, Watson, go on! It ‘s a very superficial trick, and no doubt you will soon acquire it.’

J.M. Barrie, Thomas Hardy, Rudyard Kipling, and Somerset Maugham also contributed volumes for the dollhouse, which is still on display at Windsor Castle. George Bernard Shaw declined to participate.