On Oct. 17, 1941, 73-year-old Philip Peters was found bludgeoned to death in the kitchen of his Denver home. All the doors and windows were locked. His wife, who had been away at the time, returned to the home with a housekeeper, and both heard strange sounds throughout the ensuing weeks. Finally both moved out.

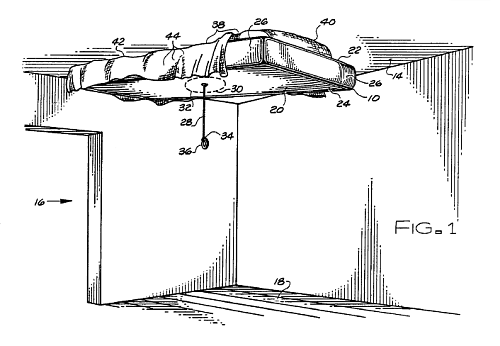

Police were checking on the vacant house the following July when they heard a noise on the second floor. An officer ran upstairs in time to see a man’s legs disappearing through a small trapdoor in the ceiling of a closet.

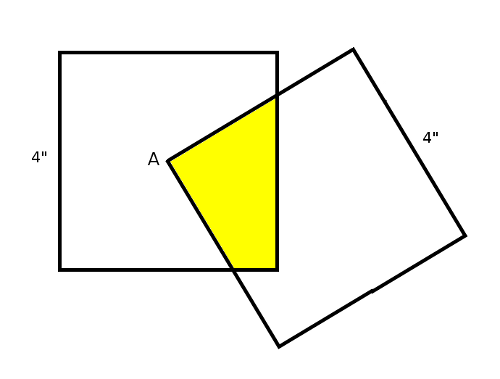

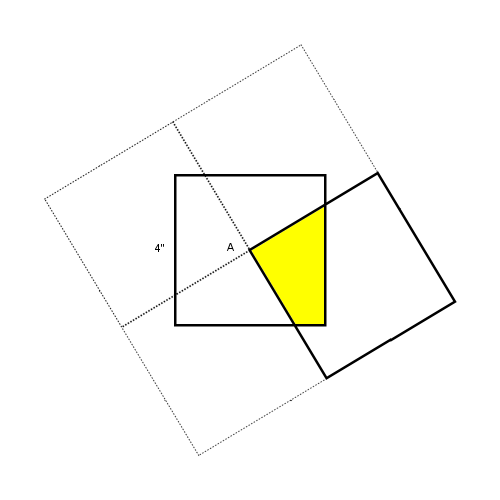

The trapdoor led to a narrow attic cubbyhole in which 59-year-old Theodore Coneys had been living for 10 months. He had broken into the house the previous September and had been living silently in the attic for a month when Peters discovered him one night at the refrigerator. After the murder he’d returned to the cubbyhole and had remained there ever since.

He confessed to the crime and was sentenced to life in prison.