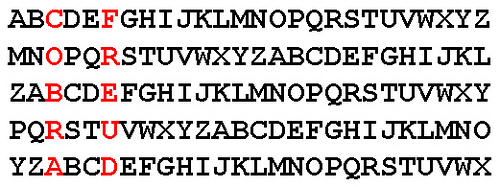

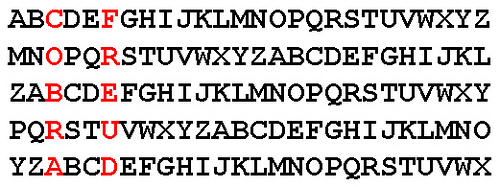

This must mean something — move each letter in COBRA three places forward in the alphabet and you get FREUD:

This must mean something — move each letter in COBRA three places forward in the alphabet and you get FREUD:

In 1987, the residents of Wilkinsburg, Pa., prepared to dig up a time capsule that had been buried in the last century. But no one could remember where it was.

In 1976, during the American bicentennial, a cross-country wagon train collected the signatures of a reported 22 million Americans to be buried at Valley Forge, Pa. But when President Ford arrived for the sealing ceremony, someone had stolen the capsule from an unattended van. It remains missing.

In 1939, MIT engineers deposited a brass time capsule beneath an 18-ton magnet used in a new cyclotron. No one has figured out how to retrieve it.

(Thanks, Luke.)

The editor of the Milford (Del.) Beacon, was shown, a few days go, a coin — a composition of copper and brass — found on the farm of Mr. Ira Hammond, about two miles from that place. It is over 600 years old, bearing, date 1178; on one side is a crown, and upon the other the words ‘Josephus, I D J-PO RT-ET-AL G-REX,’ very legible, and the work well executed. This coin is about two hundred years older than the discovery of America, and the question very naturally arises, where did it come from?

— Scientific American, 6:250, 1851

UPDATE: Another mystery solved: A reader points out this entry in the U.S.

Bureau of the Mint catalogue of coins and tokens:

Gold

16. Meia dobra, 1768. (R). 6*Jy.

JOSEPHUS.I.D.G. – PORT. ET.ALG.REX.

Laureated bust, draped, to right; below, R 1758. Rev. Garnished shield

of arms of

Portugal, crowned. Edge, wreath. 32 mm. ; 216 grs.

Probably Scientific American‘s correspondent discovered a Portuguese coin from the 18th century and misread the date. (Thanks, John.)

Why is modesty a virtue? Classically, to be virtuous is to be wise, thoughtful, and prudent. But modesty seems to depend on ignorance.

Julia Driver writes, “For a person to be modest, she must be ignorant with regard to her self-worth. She must think herself less deserving, or less worthy, than she actually is. … Since modesty is generally considered to be a virtue, it would seem that this virtue rests upon an epistemic defect.”

As Sherlock Holmes says, “To underestimate one’s self is as much a departure from truth as to exaggerate one’s own powers.”

“New and stirring things are belittled because if they are not belittled the humiliating question arises ‘Why then are you not taking part in them?'” — H.G. Wells

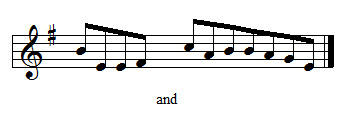

A musical joke, by J.F. Rowbotham, 1908:

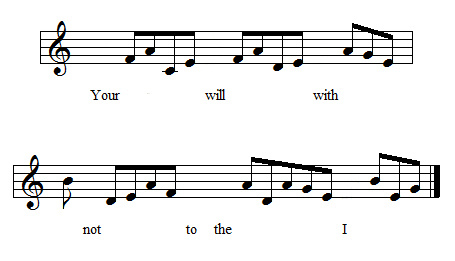

… wrote a musical wit to a friend of his, and in these terms conveyed an invitation to dinner. What is the explanation of it? “One, sharp. Beef and cabbage.” His friend, who was not behindhand at a joke, though by no means so witty as his host, replied:–

… which reads off by the same hieroglyphic: “Not a bad feed. Naturally (natural E) I will be in time.”

Rowbotham also offers this rather mean-spirited message for a vain lady:

A biologist, a statistician, and a mathematician are sitting at a cafe. Across the street, a man and a woman enter a building; ten minutes later, they emerge with a child.

“They’ve reproduced,” says the biologist.

“No,” says the statistician. “It’s an observational error. On average, 2.5 people went each way.”

“You’re both wrong,” says the mathematician. “The conclusion is obvious. If someone goes in now, the building will be empty.”

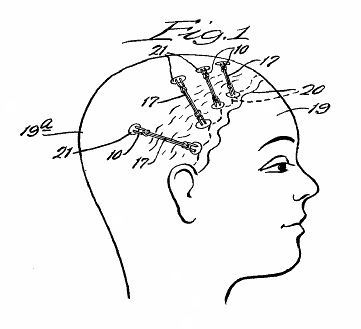

Why use creams to reduce wrinkles? Instead you can stretch your face, using Adolph Brown’s “method of minimizing facial senescence,” patented in 1952:

Anchor is hooked into the skin just beyond the hairline. … The partner hook is moved in the direction away from the face until sufficient tension forces are developed to withdraw desired amounts of skin from the face, and while this tension is maintained, the partner hook is anchored by pressing to grip the scalp.

The “rubber-like connector” between the hooks keeps the whole arrangement fairly flexible — if you don’t sneeze.

From Henry Dudeney:

A better class of puzzle is the well-known one of the Railway. If New York and San Francisco are just seven days’ journey apart, and if trains start from both ends every day at noon, how many trains coming in an opposite direction will a train leaving New York meet before it arrives at its destination at San Francisco?

Being the paper of record brings with it some odd responsibilities. On March 10, 1975, the New York Times inadvertently published the wrong dateline in its Late City editions, officially dating the day’s news “March 10, 1075.”

Modern readers would understand that this was a simple typo, of course, but the editors grew concerned that future historians might be confused to discover a Times issue from the Middle Ages. So the following day’s issue contained a historic correction:

In yesterday’s issue, The New York Times did not report on riots in Milan and the subsequent murder of the lay religious reformer Erlembald. These events took place in 1075, the year given in the dateline under the nameplate on Page 1. The Times regrets both incidents.