“Democracy is the recurrent suspicion that more than half of the people are right more than half of the time.” — E.B. White

Spirolaterals

Imagine you have a little robot that holds a pencil. Set it down on a sheet of paper and give it these instructions:

- Move forward 3 units and turn right.

- Move forward 1 unit and turn right.

- Move forward 2 units and turn left.

- Move forward 1 unit and turn left.

- Move forward 2 units and turn right.

- Repeat.

If the robot makes its turns at 90° angles, it will produce this figure:

But, remarkably, if it turns at 120° it will draw this:

“The Story of Esaw Wood”

Esaw Wood sawed wood.

Esaw Wood would saw wood!

All the wood Esaw Wood saw Esaw Wood would saw. In other words, all the wood Esaw saw to saw Esaw sought to saw.

Oh, the wood Wood would saw! And oh, the wood-saw with which Wood would saw wood.

But one day Wood’s wood-saw would saw no wood, and thus the wood Wood sawed was not the wood Wood would saw if Wood’s wood-saw would saw wood.

Now, Wood would saw wood with a wood-saw that would saw wood, so Esaw sought a saw that would saw wood.

One day Esaw saw a saw saw wood as no other wood-saw Wood saw would saw wood.

In fact, of all the wood-saws Wood ever saw saw wood Wood never saw a wood-saw that would saw wood as the wood-saw Wood saw saw wood would saw wood, and I never saw a wood-saw that would saw as the wood-saw Wood saw would saw until I saw Esaw Wood saw wood with the wood-saw Wood saw saw wood.

Now Wood saws wood with the wood-saw Wood saw saw wood.

Oh, the wood the wood-saw Wood saw would saw!

Oh, the wood Wood’s woodshed would shed when Wood would saw wood with the wood-saw Wood saw saw wood!

Finally, no man may ever know how much wood the wood-saw Wood saw would saw, if the wood-saw Wood saw would saw all the wood the wood-saw Wood saw would saw.

— W.E. Southwick

Anthologist Carolyn Wells writes, “Well, you don’t have to read it.”

Out, Damned Tot!

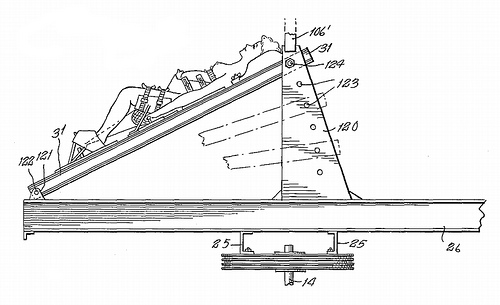

George Blonsky’s “Apparatus for Facilitating the Birth of a Child by Centrifugal Force,” patented in 1965, is pretty well self-explanatory. The modern woman lacks the muscle tone to deliver a baby easily, so we put her on a giant turntable and let G forces do the work. A glimpse through the patent abstract gives the general idea: “stretcher … handgrip … girdle … ballast … speed … forces … net … bell … handbrake … stretcher.”

A note for expectant mothers — William Potts Dewees’ 1858 Treatise on the Physical and Medical Treatment of Children includes this advice on “the treatment of the nipples”:

[T]he patient should begin to prepare these parts previously to labor, by the application of a young, but sufficiently strong puppy to the breast; this should be immediately after the seventh month of pregnancy. By this plan the nipples become familiar to the drawing of the breasts; the skin of them becomes hardened and confirmed; the milk is more easily and regularly formed; and a destructive accumulation and inflammation is prevented.

I don’t know whether Dewees actually tried this … but it seems likely he did, doesn’t it?

No, No, No

The New York Times ran a bewildering headline on May 6, 1965:

“Albany Kills Bill to Repeal Law Against Birth Control”

… a triple (quadruple?) negative.

“As you leave the town of Franklin, Pennsylvania, you encounter a sign: END BRAKE RETARDER PROHIBITION,” notes Edward Wolpow in the May 2011 issue of Word Ways. “For those for whom this is relevant, they are, presumably, able to follow the instructions quite quickly, since it is, after all, a road sign. But I still can’t figure it.”

In a 1975 interview with Business Week, Henry Kissinger said, “I am not saying that there’s no circumstances where we would not use force” against Saudi Arabia. Is this what he meant to say?

At a New York conference of linguistic philosophers in the 1950s, Oxford professor J.L. Austin noted that while a double negative often expresses a positive — as in “not unattractive” — there is no example in English of a double positive expressing a negative.

Columbia philosopher Sidney Morgenbesser, who was in the audience, sarcastically replied, “Yeah, yeah …”

Hate Mail

In Ralph Roister Doister (1553), Ralph asks a scrivener to compose a love letter to Dame Christian Custance. But when Matthew Merrygreek reads it for her, Dame Custance is shocked to hear an insulting diatribe. This is certainly not what Ralph intended, but the scrivener confirms that he copied the letter accurately, and Merrygreek read it verbatim and in full. What’s going on here?

Sweet mistress, whereas I love you nothing at all–

Regarding your substance and richness chief of all–

For your personage, beauty, demeanour and wit,

I commend me unto you never a whit.–

Sorry to hear report of your good welfare,

For (as I hear say) such your conditions are,

That ye be worthy favour of no living man,

To be abhorred of every honest man,

To be taken for a woman inclined to vice,

Nothing at all to virtue giving her due price.–

Wherefore, concerning marriage, ye are thought

Such a fine paragon, as ne’er honest man bought.–

And now by these presents I do you advertise

That I am minded to marry you in no wise.–

For your goods and substance, I can be content

To take you as ye are. If ye mind to be my wife,

Ye shall be assured, for the time of my life,

I will keep you right well from good raiment and fare–

Ye shall not be kept but in sorrow and care–

Ye shall in no wise live at your own liberty.

Do and say what ye lust, ye shall never please me;

But when ye are merry, I will be all sad;

When ye are sorry, I will be very glad;

When ye seek your heart’s ease, I will be unkind;

At no time in me shall ye much gentleness find,

But all things contrary to your will and mind,

Shall be done–otherwise I will not be behind

To speak. And as for all them that would do you wrong,

I will so help and maintain, ye shall not live long–

Nor any foolish dolt shall cumber you but I.

I, whoe’er say nay, will stick by you till I die.

Thus, good mistress Custance, the Lord you save and keep;

From me, Roister Doister, whether I wake or sleep–

Who favoureth you no less, ye may be bold,

Than this letter purporteth, which ye have unfold.

The Grid Flower

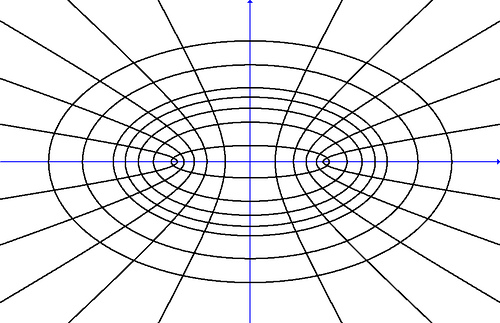

Any pair of points define an infinity of ellipses and an infinity of hyperbolas.

The ellipses do not touch one another, nor do the hyperbolas.

But every ellipse meets every hyperbola at a right angle.

Dedication

There was many years ago a Lazy Man’s Society organised in Manchester. One of the articles required that no man belonging to it should ever be in a hurry. Should he violate this article he must stand treat to the other members. Now, it happened once on a time that a doctor was driving post-haste through the streets to visit a patient. The members of the society saw him and chuckled over the idea of a treat, and on his return reminded him of his fast driving and violation of the rules. ‘Not at all,’ said the doctor. ‘The truth is, my horse was determined to go, and I felt too lazy to stop him.’ They did not catch him that time.

— Tit-Bits From All the Most Interesting Books, Periodicals, and Newspapers in the World, Oct. 22, 1881

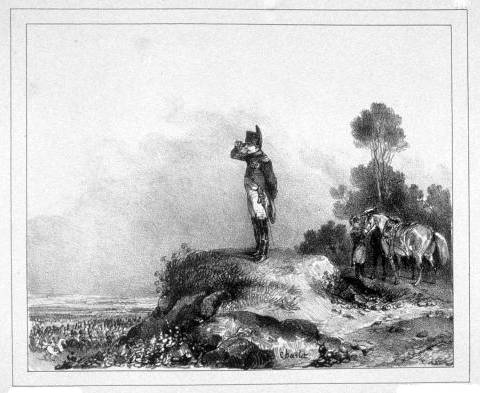

“Bonaparte and the Echo”

Bonaparte: Alone I am in this sequestered spot, not overheard.

Echo: Heard.

Bonaparte: ‘Sdeath! Who answers me? What being is there nigh?

Echo: I.

Bonaparte: Now I guess! To report my accents Echo has made her task.

Echo: Ask.

Bonaparte: Knowest thou whether London will henceforth continue to resist?

Echo: Resist.

Bonaparte: Whether Vienna and other courts will oppose me always?

Echo: Always.

Bonaparte: O, Heaven! what must I expect after so many reverses?

Echo: Reverses.

Bonaparte: What! should I, like a coward vile, to compound be reduced?

Echo: Reduced.

Bonaparte: After so many bright exploits be forced to restitution?

Echo: Restitution.

Bonaparte: Restitution of what I’ve got by true heroic feats and martial address?

Echo: Yes.

Bonaparte: What will be the fate of so much toil and trouble?

Echo: Trouble.

Bonaparte: What will become of my people, already too unhappy?

Echo: Happy.

Bonaparte: What should I then be that I think myself immortal?

Echo: Mortal.

Bonaparte: The whole world is filled with the glory of my name, you know.

Echo: No.

Bonaparte: Formerly its fame struck this vast globe with terror.

Echo: Error.

Bonaparte: Sad Echo, begone! I grow infuriate! I die!

Echo: Die!

It’s said that the Nuremberg bookseller who penned this clever bit of sedition was court-martialed and shot in 1807. Napoleon later said, “I believe he met with a fair trial.”

The Black Hole

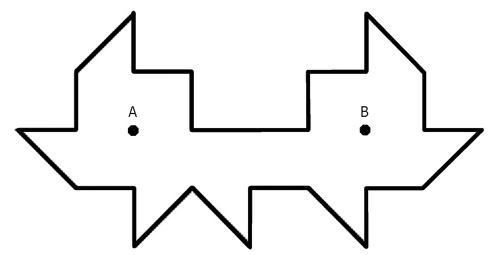

If Satan plays miniature golf, this is his favorite hole. A ball struck at A, in any direction, will never find the hole at B — even if it bounces forever.

The idea arose in the 1950s, when Ernst Straus wondered whether a room lined with mirrors would always be illuminated completely by a single match.

Straus’ question went unanswered until 1995, when George Tokarsky found a 26-sided room with a “dark” spot; two years later D. Castro offered the 24-sided improvement above. If a candle is placed at A, and you’re standing at B, you won’t see its reflection anywhere around you — even though you’re surrounded by mirrors.