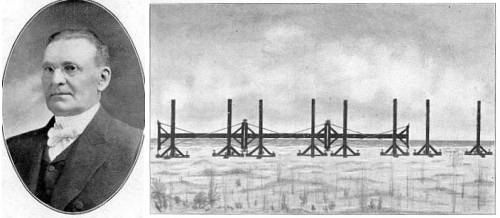

In 1897, Cyrus Teed proved that we inhabit a hollow earth. He did this by building a “Rectilineator,” essentially a giant straightedge that could extend a perfectly straight line across a great distance. On a convex earth this line should rise gradually in altitude as the earth’s surface falls away from it. But in his trials in Florida, Teed found that the line ran into the earth after 4 1/8 miles, proving that the surface is concave, in accord with his “Koreshan cosmogony.”

The extension of the arc of curvature which we have measured and have demonstrated to be concave, forms a circumference of about 25,000 miles; which conclusion, taken in connection with all the astronomical, geographical, and geodetic facts obtained by centuries of observation and survey, demonstrates that the surface of the earth upon which we live is the inner surface of a great cell about 8,000 miles in diameter.

“No one has ever seriously attempted either to debunk or to repeat the Rectilineator experiment,” writes John Michell in Eccentric Lives and Peculiar Notions, “but it is natural for those who can not bring themselves to accept its results to wonder how they were obtained. The Rectilineator apparatus, though cumbersome, was scientifically sound, and so was the principle behind its use, and one can hardly suppose that the Koreshan surveyors, who lived by the doctrines of their leader, were engaged in an elaborate conspiracy of deception. Perhaps the answer lies in the malleable, obliging nature of the universe, which reflects every image projected upon it and gives every experiment a tendency to gratify the experimenter.”