“A portrait is a painting with something wrong with the mouth.” — John Singer Sargent

“A portrait is a painting with something wrong with the mouth.” — John Singer Sargent

Subtitled “A Novel in Woodcuts,” Lynd Ward’s 1929 parable Gods’ Man unfolds in images, making it an important forebear of the modern graphic novel. A young artist makes his way to the big city, where a masked stranger gives him a magic paintbrush. The adventures that follow remark on the roles of love and commerce in an artist’s life; in the end the stranger returns to claim a reward.

Despite its unusual format, Ward’s book sold more than 20,000 copies during the Depression, and he followed it up with five more wordless novels. When he died in 1985, he was at work on an ambitious seventh, which Rutgers published in 2001.

We instinktivly shrink from eny chaenj in whot iz familyar; and whot kan be mor familyar dhan dhe form ov wurdz dhat we hav seen and riten mor tiemz dhan we kan posibly estimaet? We taek up a book printed in Amerika, and honor and center jar upon us every tiem we kum akros dhem; nae, eeven to see forever in plaes ov for ever atrakts our atenshon in an unplezant wae. But dheez ar iesolaeted kaesez; think ov dhe meny wurdz dhat wood hav to be chaenjd if eny real impruuvment wer to rezult. At dhe furst glaans a pasej in eny reformd speling looks ‘kweer’ or ‘ugly’. Dhis objekshon iz aulwaez dhe furst to be maed; it iz purfektly natueral; it iz dhe hardest to remuuv. Indeed, its efekt iz not weekend until dhe nue speling iz noe longger nue, until it haz been seen ofen enuf to be familyar.

— Walter Ripman and William Archer, New Spelling, 1948

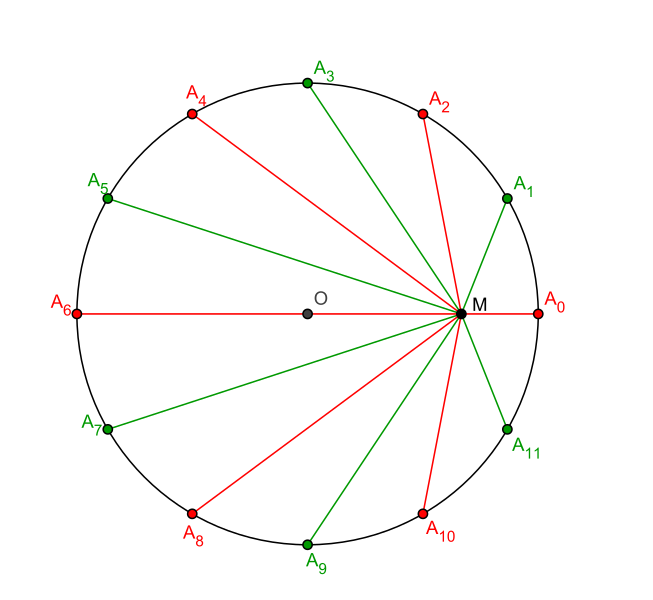

The product of the distances from N equally spaced points on a unit circle to a point M that lies on the x axis at distance x from circle origin O and on a line passing through the first point, A0, on the circle equals 1 – xN.

Discovered by Roger Cotes (1682-1716). Here’s a proof.

From reader Dave King:

A certain young lady of Prinknash

Was looking decidedly thinknash.

Her diet restriction

Had proved an addiction

And caused her to swiftly diminknash.

A hungry young student of Norwich

Went into his larder to forwich.

For breakfast he usually

Had bacon or muesli

But today he would have to have porwich.

An ethical diner at Alnwick

Was suddenly put in a palnwick

“This coffee you’ve made

Are you sure it’s Fair Trade?

And I must insist that it’s orgalnwick!”

A Science don, Gonville and Caius,

Kept body parts in his deep fraius.

He didn’t remember

And one dark November

He ate them with cabbage and paius.

A Frenchman now living at Barnoldswick

Was terribly partial to garnoldswick.

The smell of his breath

Drove one lady to death;

She fell from the ramparts at Harnoldswick.

A forceful young prisoner from Brougham

Was confined to a windowless rougham,

So, venting his feelings,

He bashed through the ceiling,

Dispelling the gathering glougham.

(Thanks, Dave.)

The 1937 edition of Webster’s Universal Dictionary of the English Language contains this peculiar entry:

jungftak (jŭngf´ täk) n. a fabled Persian bird, the male of which had only one wing, on the right side, and the female only one wing, on the left side; instead of the missing wings, the male had a hook of bone, and the female an eyelet of bone, and it was by uniting hook and eye that they were enabled to fly, — each, when alone, had to remain on the ground.

This appears to be neither an error nor a trap to catch copyright thieves. When scholar Richard Rex asked about it, an associate editor at the dictionary replied, “[W]e have gone through a good many sources and jungftak simply does not show up. It is quite a curiosity, for the various accounts of Persian mythology do not describe such a bird even under another name.” The entry disappears from editions after 1943. Probably it was a joke, but the story behind it is lost.

(Richard Rex, “The Incredible Jungftak,” American Speech 57:4 [Winter 1982], 307-308.)

06/19/2024 UPDATE: Reader Nick Hare offers another fantastic bird: the oozlum, which flies in smaller and smaller circles until it disappears up its own backside. Wikipedia observes drily that this behavior “adds to its rarity.”

06/21/2024 UPDATE: Wow, this is really interesting. Reader Edward White informs me that there’s a bird in Chinese mythology, the biyiniao or linked-wing bird, that closely resembles the jungftak — each biyiniao has one eye and one wing, so they have to pair up to fly. The bird is used as a symbol of married love in poems. Can this be a coincidence?

Wha lies here? I Johnny Dow. Hoo! Johnny, is that you? Ay, man, but a'm dead now.

— Edinburgh epitaph, quoted in Horatio Edward Norfolk, Gleanings in Graveyards, 1861

D.C.B. Marsh proposed this problem in the American Mathematical Monthly in 1957:

“Solve a3 – b3 – c3 = 3abc, a2 = 2(b + c) simultaneously in positive integers.”

There are a number of ways to go about this, but Raymond Huck of Marietta College found a strikingly simple one. 3abc is positive, so the first equation tells us immediately that b < a and c < a. Add these two facts together and we get b + c < 2a, and hence 2(b + c) < 4a. Substituting this conveniently into the second equation, we learn that a2 < 4a and a < 4. The second equation also shows that a is an even number, so a must be 2, and b and c, which are smaller, must both be 1.

(“Solutions,” American Mathematical Monthly 65:1 [January 1958], 43-46, Problem E1266, via Ross Honsberger, Mathematical Morsels, 1979.)

In 2006, German entomologist Jochen-P. Saltin discovered a new species of rhinoceros beetle in Peru, which he dubbed Megaceras briansaltini.

Remarkably, the insect’s horn closely resembles that of Dim, the blue rhinoceros beetle in the Disney film A Bug’s Life, which was released eight years earlier.

“I know of no dynastine head horn that has ever had the shape of the one seen in M. briansaltini, and so its resemblance to a movie character seems like a case of nature mimicking art … or what could be referred to as ‘the Dim Effect,'” wrote entomologist Brett C. Ratcliffe.

“There are numerous examples of art mimicking nature (paintings, sculpture, etc.), but that cannot be the case here, because there had never been a known rhinoceros beetle in nature upon which the creators of Dim could have used as a model for the head horn. In my experience, then, Dim was the first ‘rhinoceros beetle’ to display such a horn, and the discovery of M. briansaltini, a real rhinoceros beetle, came later.”

(Brett C. Ratcliffe, “A Remarkable New Species of Megaceras From Peru [Scarabaeidae: Dynastinae: Oryctini]. The ‘Dim Effect’: Nature Mimicking Art,” The Coleopterists Bulletin 61:3 [2007], 463-467.)

In the 1970s, San Francisco painting contractor Bill Holland discovered he could save money on business cards by listing himself as Zachary Zzzra in the local telephone directory and telling potential customers to find his number at the end of the book.

This worked well until he was displaced by a Zelda Zzzwramp. He changed his name to Zachary Zzzzra but was overtaken by Vladimir Zzzzzzabakov. So in 1979 he pulled out all stops and became Zachary Zzzzzzzzzra.

Victory brought its trials. “People making illegal calls from phone booths look up the last name in the book and charge them to me,” he admitted to Time. “I don’t pay a damn one of them.”

06/17/2024 UPDATE: Reader Nick Semanko adds that in 1964 two Rhode Island politicians, Raphael R. Russo and Mario Russillo, changed their names to aRusso and aRussillo so that they could appear at the top (technically the left) of the ballot. aRussillo won and aRusso lost.

Four years later the two faced one another for the position of town administrator of Johnston. aRussillo added another a to his name (becoming aaRussillo) and won, though aRusso eventually succeeded him. aaRussillo dropped the extra letters from his name in 1995, but aRusso kept his to his death in 1999. (Thanks, Nick.)