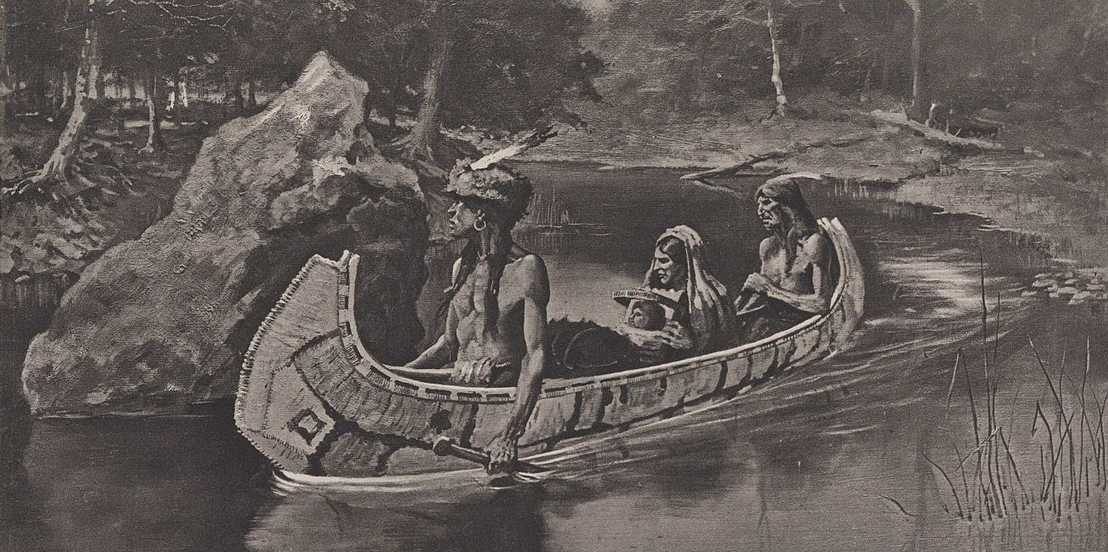

In 2004 Stanford physicist R.B. Laughlin wrote a 12-page poem critiquing of the theory of resonating valence bonds. He set it in trochaic tetrameter, after Longfellow’s Song of Hiawatha:

What ensued was simply awesome,

Destined to go down in legend.

They proposed a cuprate theory

So magnificent in concept,

So much bolder than the others

That it blasted them to pieces

Like some big atomic warhead,

So outshined them in its glory

Like a nova in the heavens

That it blinded any person

Who would dare to gaze upon it.

Cuprates did these things, it stated,

Just because a quirk of nature

Made them like the Hubbard model,

Which, as had been long established,

Did some things quite fundamental,

Not yet known to modern science,

Which explained the crazy data,

So to understand the cuprates

One would have to solve this model.

How colossal! How stupendous!

It was absolutely foolproof!

No one could disprove this theory

With existing mathematics

Or experimental data

For exactly the same reasons

Nor could they admit they couldn’t,

So they’d spend their whole lives trying,

Blame themselves for being so stupid,

And pay homage in each paper

With the requisite citation!

The whole thing is here. (Thanks, Daniele.)

Related: Mark Twain’s father, a justice of the peace, once told his son that there was more poetry in a warranty deed than in Longfellow’s verse. So Twain “took the stupid warranty deed itself and chopped it up into Hiawathian blank verse, without altering or leaving out three words, and without transposing six”:

THE STORY OF A GALLANT DEED.

THIS INDENTURE, made the tenth

Day of November, in the year

Of our Lord one thousand eight

Hundred six-and-fifty,

Between JOANNA S.E. GRAY

And PHILIP GRAY, her husband,

Of Salem City in the State

Of Texas, of the first part,

And O.B. Johnson, of the town

Of Austin, ditto, WITNESSETH:

That said party of first part,

For and in consideration

Of the sum of Twenty Thousand

Dollars, lawful money of

The U.S. of Americay,

To them in hand now paid by said

Party of the second part,

The due receipt whereof is here

By confessed and acknowledg-ed,

Have Granted, Bargained, Sold, Remised,

Released and Aliened and Conveyed,

Confirmed, and by these presents do

Grant and Bargain, Sell, Remise,

Alien, Release, Convey, and Con-

Firm unto the said aforesaid

Party of the second part,

And to his heirs and assigns

Forever and ever, ALL

That certain piece or parcel of

LAND situate in city of

Dunkirk, county of Chautauqua,

And likewise furthermore in York State,

Bounded and described, to-wit,

As follows, herein, namely:

BEGINNING at the distance of

A hundred two-and-forty feet,

North-half-east, north-east-by-north,

East-north-east and northerly

Of the northerly line of Mulligan street,

On the westerly line of Brannigan street,

And running thence due northerly

On Brannigan street 200 feet,

Thence at right angles westerly,

North-west-by-west-and-west-half-west,

West-and-by-north, north-west-by-west,

About —

That’s as far as he got in reciting it to his father. “I kind of dodged, and the boot-jack broke the looking glass. I could have waited to see what became of the other missiles if I had wanted to, but I took no interest in such things.”