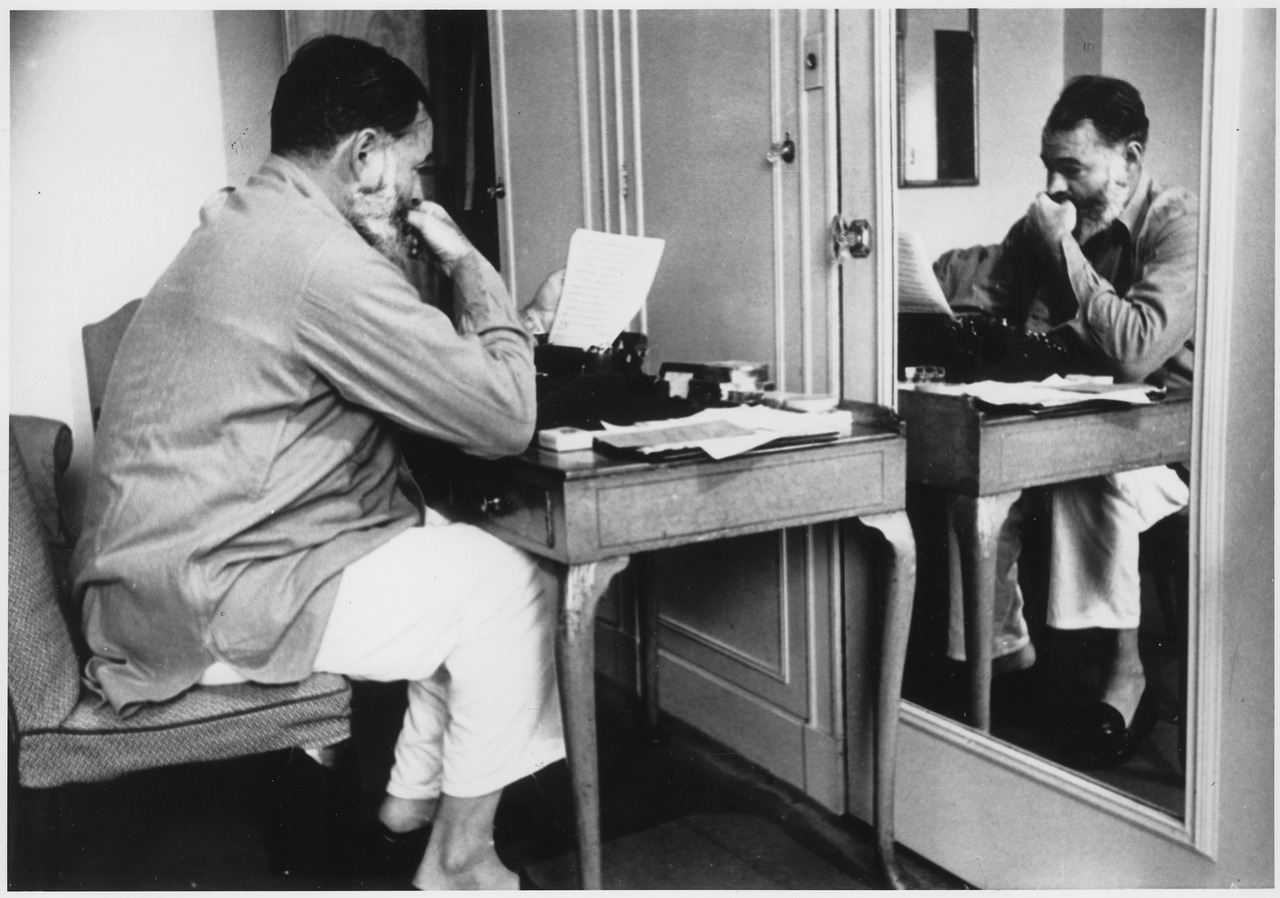

Paris could be very fine in the winter when it was clear and cold and they were young and in love but that winter of 1924 they quarreled badly and she left for good. Paris, the city of light, turned dark and sodden with sadness. But it was still a damn fine place and he hated to leave it so he sat in the cafés all day and drank wine and thought about writing clean short words on bright white paper.

He preferred Café des Amateurs, on the Place St-Michel. The waiters in their long aprons respected him and he did good work there, defeating them all in the arm wrestling and the drinking and the dominoes and the boxing. They told him timeless stories of love and cruelty and death. That was good, because his Michigan stories had dried up, his jockeys and boxers had worn out, and sometimes he worried his oeuvre might be over.

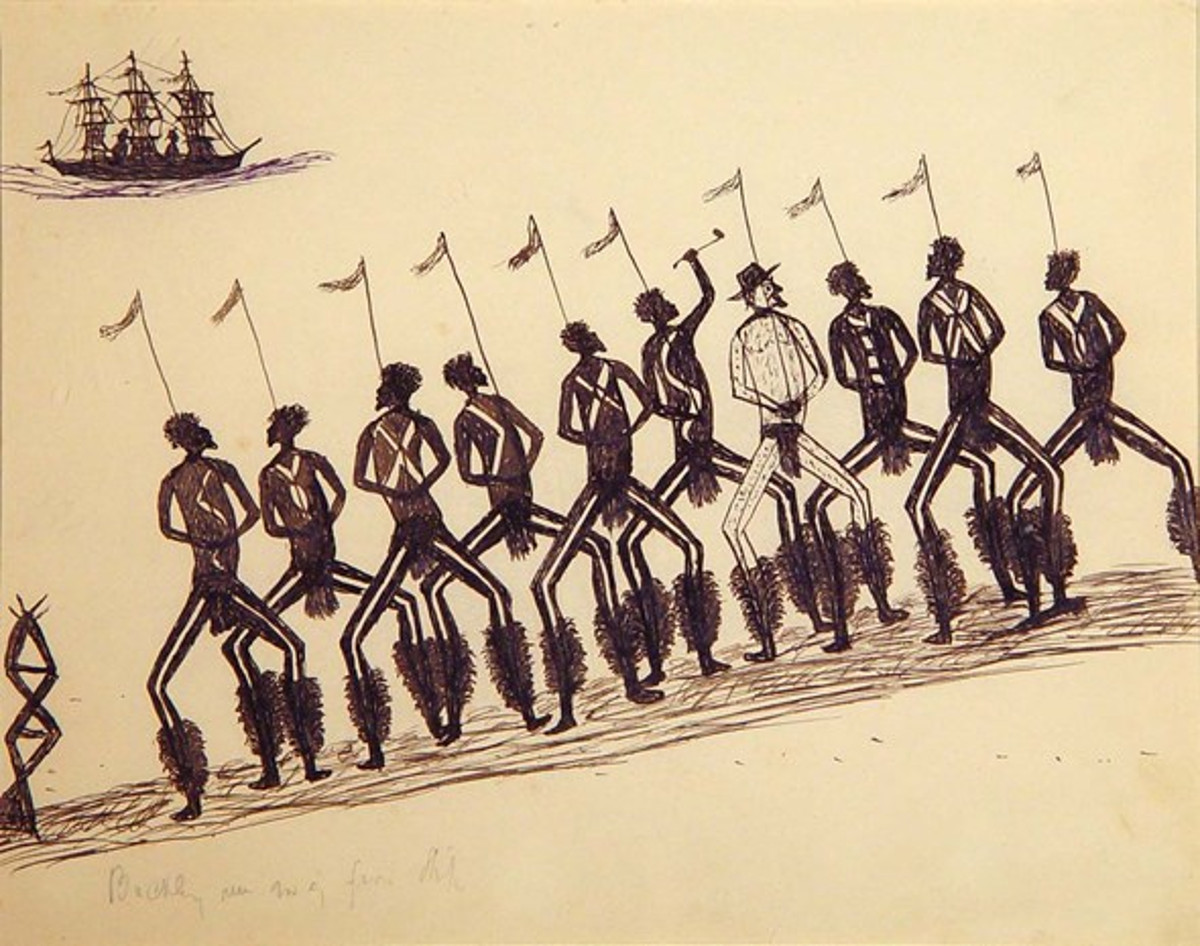

One afternoon in late autumn two gypsies came into the café, a ragged old man and his daughter. She carried a crystal ball between her arms. They went table to table telling fortunes. Soon they came to him. Dark eyes stared at his palm, then into the ball. Two fair arms well cradled it in her lap.

‘Guapa, I am not one for whom the ball tells –‘ he started, but she put a finger to his lips. She studied his face. Her dark eyes were like deep forest pools where trout the color of pebbles hang motionless in the cool flowing eddies, waiting for the good larvae, the tasty larvae. Sun-burned, confident, loving eyes the color of the sea. He wrote that down.

‘Inglés, my ball shows what you must write.’

‘Americain.’ It was like saying hello to a statue. He wrote that down, too.

‘Picture this,’ she started, ‘First I see a corpse in the Louvre, by the Mona Lisa. A gruesome ritual murder. The police suspect you, an obscure professor. You flee, through the Tuilleries, then across the river.’

‘Into the trees?’

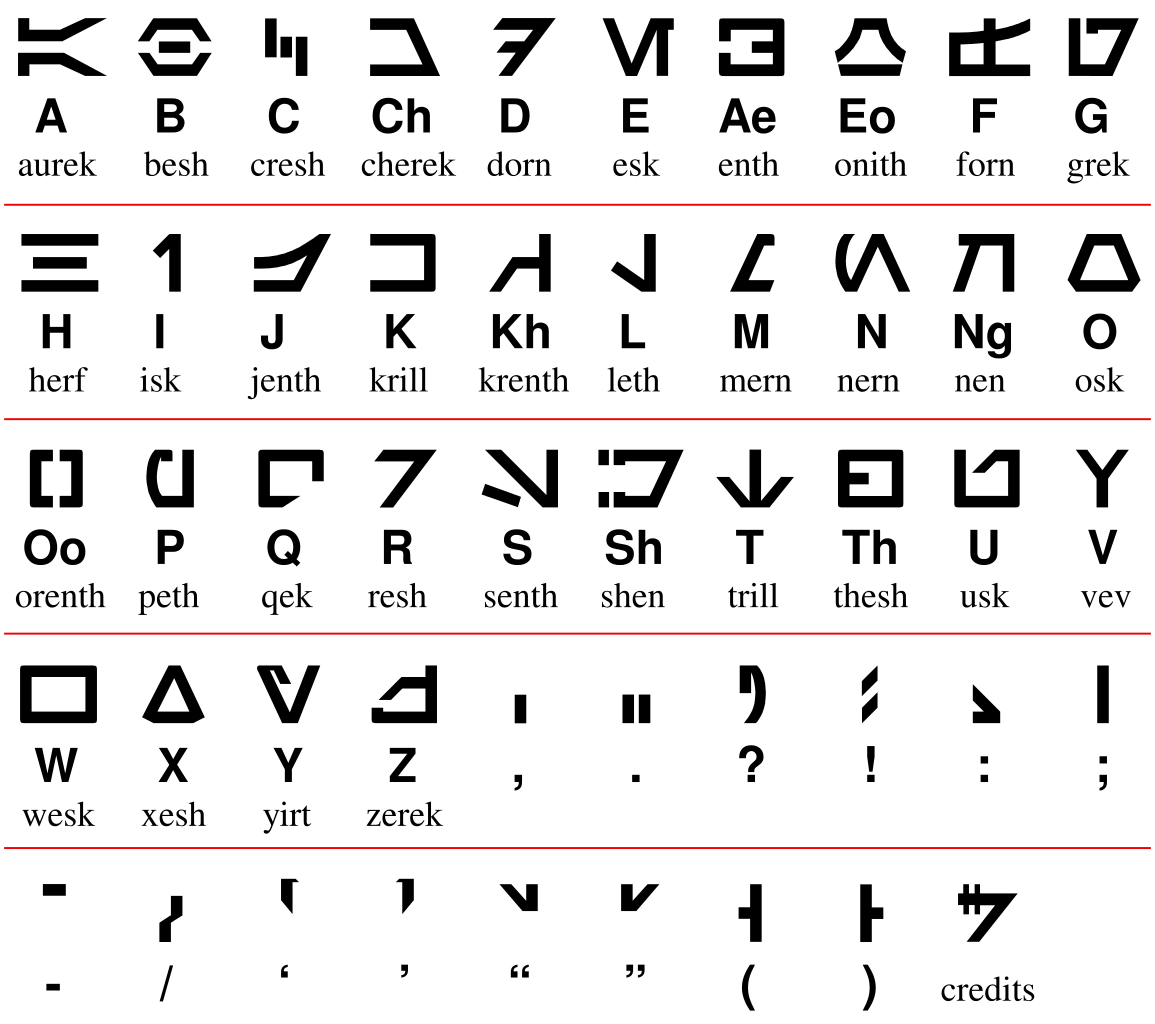

‘Murders in churches, arcane symbols and codes, Opus Dei, Swiss bankers, split-second escapes, powerful sects …’

‘Powerful sex?’

She paused. ‘I see a mysterious redhead at your side.’

‘Powerful sex?’

Her eyes found his. ‘I see a major motion picture.’

‘No,’ he shook his head earnestly. ‘Not now. I must master the art of narration in the best and simplest way. Lean hard narrative prose.’

She rolled her eyes, sunburned eyes. ‘Isn’t it pretty to think so …’

‘I write terrific stuff here, guapa,’ he said, writing that down. ‘True sentences. Not the words above the urinal.’

‘Don’t call me guapa, Papa.’

‘Drop the Papa, guapa.’

‘Whatever,’ she sighed and turned to the ball again. ‘Try this, loser Americain. An old fisherman loves baseball. He catches a big fish, but sharks eat it.’

He slapped her hard across the ear. It was a good ear, sunburned and confident. And just like that, the old man and the seer disappeared.

To celebrate his win, Davis said he was “toying with the idea of growing a beard and fishing Lake Michigan for marlin.”