ullage

n. the amount a container lacks of being full

Given a 5-gallon jug, a 3-gallon jug, and a limitless supply of water, how can you measure out exactly 4 gallons?

ullage

n. the amount a container lacks of being full

Given a 5-gallon jug, a 3-gallon jug, and a limitless supply of water, how can you measure out exactly 4 gallons?

subsannation

n. mockery or derision

quoz

n. an odd or ridiculous person or thing

cursitate

v. to run hither and thither

mattoid

adj. displaying erratic behaviour

periergia

n. bombastic or laboured language

galimatias

n. confused language, meaningless talk, nonsense

taigle

v. to impede or hinder; hence, to fatigue; weary

obtrect

v. to disparage or decry

A paragraph from an unnamed “publication from a leading geographical society”:

The examples given suggest that the multiformity of environmental apprehension and the exclusivity of abstract semantic conceptions constitute a crucial distinction. Semantic responses to qualities, environmental or other, tend to abstract each individual quality as though it were to be considered in isolation, with nothing else impinging. But in actual environmental experience, our judgements of attributes are constantly affected by the entire milieu, and the connectivities such observations suggest reveal this multiform complexity. Semantic response is generally a consequence of reductive categorization, environmental response or synthesizing holism.

In The Jargon of the Professions, Kenneth Hudson suggests that the authors “should be locked up without food or water until they can produce an acceptable translation.” In Secret Language, Barry J. Blake adds, “I think the passage simply means that in experiencing the environment we need to look at it as a whole rather than at particular properties, though I am at a loss to decode the first sentence.”

pernicity

n. swiftness, quickness, agility

discoverture

n. the state of not having a husband

supersalient

adj. leaping upon

desponsate

adj. married

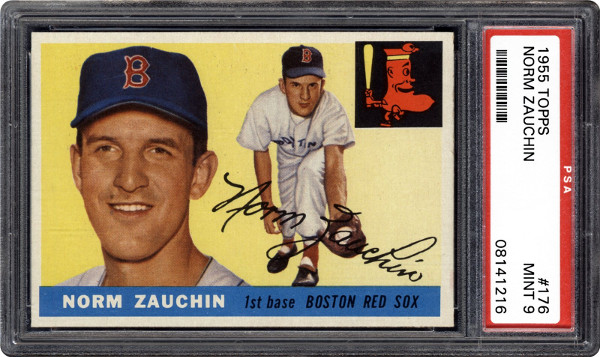

The Fenway Millionaires also have a ‘sleeper’ in Norm Zauchin, a massive fellow just out of the Army. Don’t underestimate him. When he was at Birmingham he pursued a twisting foul ball into a front row box. He clutched frantically. He missed grabbing the ball but he did grab a girl, Janet Mooney. This might not be considered a proper introduction by Emily Post but it worked for Zauchin. He married the gal. Nope. Don’t underestimate an opportunist like that.

— Arthur Daley, “Life Among the Millionaires,” New York Times, March 11, 1954

cynocephalous

adj. dog-headed

vectitation

n. the action of carrying

munerary

adj. relating to gifts

jumelle

n. a pair of things joined

ambagious

adj. circumlocutory

polylogize

v. to talk a great deal

asteism

n. genteel irony, polite and ingenious mockery

The prolixity of counsel has provoked much good-and-bad-humored interruption from the Bench; and first for the good:– In Mr. Justice Darling’s court a few years ago, counsel, in cross-examining a witness, was very diffuse, and wasted much time. He had begun by asking the witness how many children she had, and concluded by asking the same question. Before the witness could reply, Justice Darling interposed with the suave remark — ‘When you began, she had three.’

— Central Law Journal, Sept. 13, 1912

mournival

n. a set of four things or people

luculent

adj. of compositions: brilliant, admirable; hence of a writer or orator

chrysostomic

adj. golden-mouthed

palmary

adj. holding the first or highest place; pre-eminent; excellent

obtest

v. to call heaven to witness; to protest against

proditor

n. a traitor; a betrayer

Is a union breaking the law if it posts a giant inflatable rat outside an employer’s facility? No, it’s not, according to a 2011 decision by the National Labor Relations Board. The Sheet Metal Workers’ Union had sought to dissuade a hospital from using non-union workers by stationing a 16-foot rat near the building’s entrance. The NLRB held that the “the use of the stationary Giant Rat (i) constituted peaceful and constitutionally protectable expression, (ii) did not involve confrontational conduct that would qualify as unlawful picketing, and (iii) did not qualify as nonpicketing conduct that was otherwise unlawfully coercive.”

The “rat collosi” are multiplying (gallery). Let’s hope they don’t stage an uprising themselves someday.

ubiety

n. the state of occupying a certain place or position; the place in which a person or thing is; “whereness”

forfex

n. a pair of scissors