Futility Closet: An Idler’s Miscellany of Compendious Amusements collects some of my favorite finds in a career of dedicated curiosity-seeking: lawyers struck by lightning, wills in chili recipes, a lost manuscript by Jules Verne, dreams predicting horse race winners, softball at the North Pole, physicist pussycats, 5-year-olds in the mail, camels in Texas, balloons in the arctic, a lawsuit against Satan, starlings amok, backward shoes, revolving squirrels, Dutch Schultz’s last words, Alaskan mirages, armored baby carriages, pig trials, rivergoing pussycats, a scheme to steal the Mona Lisa, and hundreds more.

Plus a selection of the curious words, odd inventions, and quotations that are regular features on the site, as well as 24 favorite puzzles and a preface explaining how Futility Closet came to be and how I come up with this stuff.

Available now on Amazon!

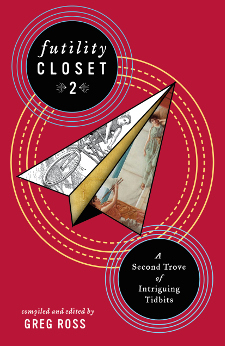

Another helping of Futility Closet’s best — hundreds of entertaining oddities in history, literature, language, art, philosophy, and mathematics, the perfect gift for people who are impossible to buy gifts for.

Futility Closet 2: A Second Trove of Intriguing Tidbits contains hundreds of hand-picked favorites from the site’s burgeoning archive of the marvelous, the diverting, and the strange: joyous dogs, soul-stirring Frenchmen, runaway balloons, U-turning communists, manful hummingbirds, recalcitrant Ws, intractable biplanes, hairless trombonists, abusive New Zealanders, unreconstituted cannibals, mysterious blimps, thrice-conscripted Koreans, imaginary golf courses, irate Thackerays, and hundreds more. Plus the amusing inventions, curious words, and beguiling puzzles that regularly entertain millions of website visitors and podcast listeners.

Buy it now on Amazon!