On Sept. 13, 1858, ex-slave John Price was accosted on the streets of Oberlin, Ohio, by a U.S. marshal, who took him to nearby Wellington, hoping to return him to Kentucky as a fugitive. Ohio was a free state, but the federal government had committed to helping slaveholders retrieve their runaway slaves.

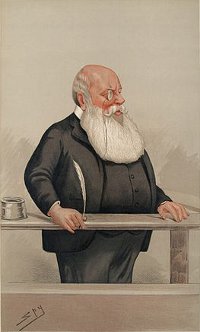

When word of Price’s abduction spread, a large crowd of Oberlin townspeople surrounded the marshal’s hotel and demanded his release, eventually breaking in to return him to Oberlin. Thirty-seven of the rescuers were indicted, including black abolitionist Charles Langston, who made this impassioned speech at his trial:

But I stand up here to say, that if for doing what I did on that day at Wellington, I am to go to jail six months, and pay a fine of a thousand dollars, according to the Fugitive Slave Law, and such is the protection the laws of this country afford me, I must take upon my self the responsibility of self-protection; and when I come to be claimed by some perjured wretch as his slave, I shall never be taken into slavery. And as in that trying hour I would have others do to me, as I would call upon my friends to help me; as I would call upon you, your Honor, to help me; as I would call upon you [to the district attorney], to help me; and upon you [to Judge George Bliss], and upon you [to his counsel], so help me GOD! I stand here to say that I will do all I can, for any man thus seized and help, though the inevitable penalty of six months’ imprisonment and one thousand dollars’ fine for each offense hangs over me! We have a common humanity. You would do so; your manhood would require it; and no matter what the laws might be, you would honor yourself for doing it; your friends would honor you for doing it; your children to all generations would honor you for doing it; and every good and honest man would say, you had done right!

This was met with “great and prolonged applause, in spite of the efforts of the Court and the Marshal.” Langston was convicted but given a reduced sentence of 20 days. His eloquence was hereditary, apparently — his grandson was Langston Hughes.