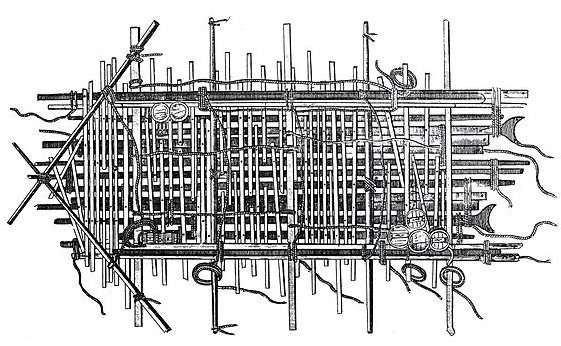

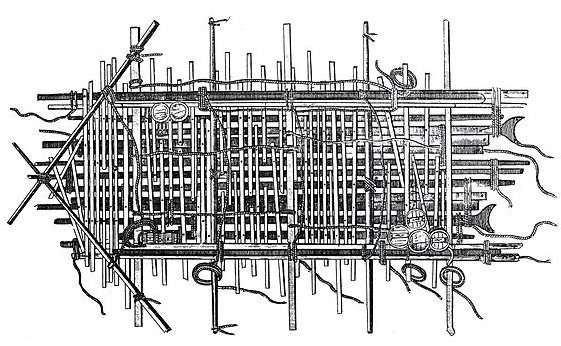

En route to Senegal in 1816, the French frigate Méduse ran aground on a reef. The six boats were quickly filled, so those who remained lashed together a raft from topmasts, yards, and planks, and 147 people crowded onto a space 65 feet long and 23 wide, hoping to be towed to the African coast 50 miles away. (Seventeen crew and passengers remained aboard the Méduse.)

The raft sank 3 feet under their combined weight, and the tow line quickly parted. Rather than try to rescue them, the boats sailed on to the Senegalese capital. On the first night, 20 men drowned. On the second, some soldiers broke open a cask of wine and mutinied; in the ensuing melee, at least 60 were killed. By the following afternoon, the 67 who remained were gnawing sword belts to reduce their hunger. Eventually they descended on a corpse embedded among the logs of the raft. “We shudder with horror on finding ourselves under the necessity of recording that which we put into practice,” one wrote later.

On the fourth day, 48 remained, and that night a second mutiny killed 18 more. By the seventh day their numbers had dropped to 27 and they decided that their provisions would support only 15, so the 12 weakest were thrown to the sharks. The last 15 survived for 13 miserable days, living on garlic cloves, a lemon, and occasionally a flying fish. They were finally spotted by the brig Argus, a moment immortalized by Théodore Géricault (below).

Of the 17 who had remained aboard the Méduse, three survived. One told his story to a survivor of the raft journey, who wrote, “They lived in separate corners of the wreck, which they never quitted but to look for food, and this latterly consisted only of tallow and a little bacon. If, on these occasions, they accidentally met, they used to run at each other with drawn knives.”

For all this, the captain of the Méduse was imprisoned for only three years, an occasion for lasting controversy in French politics. “It is more difficult to escape from the injustice of man,” wrote one commentator, “than the fury of the sea.”