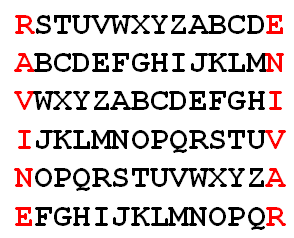

Brother Jacques Percher, “a very excellent man of the old time,” had a painting made for his chapel showing that good is the very opposite of evil. At one side was a picture of an angel, with the words “Read the right side and you will be saved.” Under that was this inscription:

Delicias fuge, ne frangaris crimine, verum

Coelica tu quaeras, ne male dispereas,

Respicias tua, non cujusvis quaerito gesta

Carpere, sed laudes, nec preme veridicos.

Judicio fore te praesentem conspice toto

Tempore, nec Christum, te rogo, despicias:

Salvificum pete, nec secteris daemonia; Christum

Dilige, nequaquam tu mala concupito.

Shun pleasures of the flesh, lest you be broken by crime; seek the things of heaven, lest your end be an evil one; consider your own deeds, and do not seek to slander someone else’s, but praise them, and do not suppress those who speak the truth; always realize that you must stand before a judgment; I beg you, do not despise Christ, seek him who gives salvation, and do not follow the devil; love Christ, and do not lust at all after evil.

At the other side was a picture of the devil with the words “Read the wrong side and you will be damned.” Here the first inscription was reversed word for word, producing an entirely different meaning:

Concupito mala tu, nequaquam dilige Christum,

Daemonia secteris, nec pete salvificum;

Despicias, rogo te, Christum, nec tempore toto

Conspice praesentem te fore judicio:

Veridicos preme, nec laudes, sed carpere gesta

Quaerito cujusvis, non tua respicias,

Dispereas male, nec quaeras tu coelica; verum

Crimine frangaris, ne fuge delicias.

Lust after evil, and do not at all love Christ; you follow the devil, do not seek him who gives salvation; despise Christ, I beg you, and realize that never will you stand before a judgment; suppress those who speak the truth, and do not praise the deeds of anyone, but seek to slander them; do not consider your own; let your end be an evil one, do not seek the things of heaven; let yourself be broken by crime, do not shun pleasures of the flesh.

“It must have taken the brother a long time to compose this,” writes George Wakeman, “but he probably did it with a holy purpose, and as a recreation from more onerous duties.”

See also A Bilingual Palindrome.