aknee

adj. on one’s knees

procation

n. a marriage suit

aknee

adj. on one’s knees

procation

n. a marriage suit

cohonestation

n. honouring with one’s company

William Cobbett, a writer who was to plague Noah for many years, probably invented one piece of Websterian apocrypha. Dr. Benjamin Rush, whom Noah had cultivated, supposedly met him upon his arrival and said: ‘How do you do, my dear friend. I congratulate you on your arrival in Philadelphia.’

‘Sir,’ Webster allegedly replied, ‘you may congratulate Philadelphia on the occasion.’

— John S. Morgan, Noah Webster, 1975

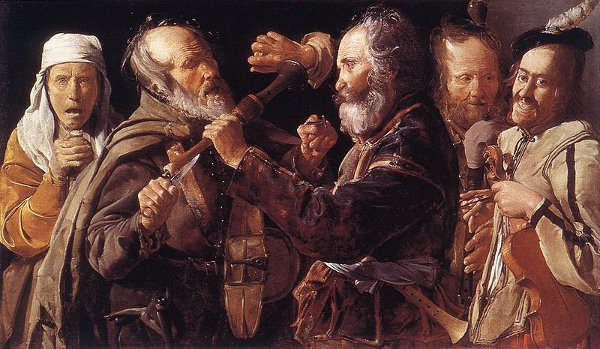

vitilitigate

v. to be particularly quarrelsome

rixation

n. a quarrel or argument

cavillation

n. the raising of quibbles

snoutband

n. one who constantly contradicts his companions

consenescence

n. the growing old together

tonitruation

n. thundering

Finnegans Wake is punctuated by ten thunderclaps, which occur at moments of crisis in the text. “A situation is presented, developed, and subjected to increasing stress until, with the thunder, a collapse, and suddenly a complementary situation that was latent in the first is seen to be in place,” writes scholar Eric McLuhan.

First thunderclap:

bababadalgharaghtakamminaronnonnbronntonnerronnuonnthunn-

trobarrhounawnskawntoohoohoordenenthurknuk

Second:

Perkodhuskurunbarggruauyagokgorlayorgromgremmitghundhurthru-

mathunaradidillifaititillibumullunukkunun

Third:

klikkaklakkaklaskaklopatzklatschabattacreppycrottygraddaghsemmih-

sammihnouithappluddyappladdypkonpkot

Fourth:

Bladyughfoulmoecklenburgwhurawhorascortastrumpapornanennykock-

sapastippatappatupperstrippuckputtanach

Fifth:

Thingcrooklyexineverypasturesixdixlikencehimaroundhersthemagger-

bykinkinkankanwithdownmindlookingated

Sixth:

Lukkedoerendunandurraskewdylooshoofermoyportertooryzooysphalna-

bortansporthaokansakroidverjkapakkapuk

Seventh:

Bothallchoractorschumminaroundgansumuminarumdrumstrumtrumina-

humptadumpwaultopoofoolooderamaunsturnup

Eighth:

Pappappapparrassannuaragheallachnatullaghmonganmacmacmacwhack-

falltherdebblenonthedubblandaddydoodled

Ninth:

husstenhasstencaffincoffintussemtossemdamandamnacosaghcusaghhobix-

hatouxpeswchbechoscashlcarcarcaract

Tenth:

Ullhodturdenweirmudgaardgringnirurdrmolnirfenrirlukkilokkibaugiman-

dodrrerinsurtkrinmgernrackinarockar

Like everything in Joyce, the claps’ meaning is open to question, but they’re not arbitrary: Each of the first nine words contains exactly 100 letters, and the tenth has 101. Joyce, who called thunder “perfect language,” had apparently adjusted the spelling of the thunderclaps as the book took shape: McLuhan found tick marks in Joyce’s galley proofs, “the only evidence of actual letter-counting I have found in any of the manuscripts, typescripts, proofs, and galleys.”

(Eric McLuhan, The Role of Thunder in Finnegans Wake, 1997.)

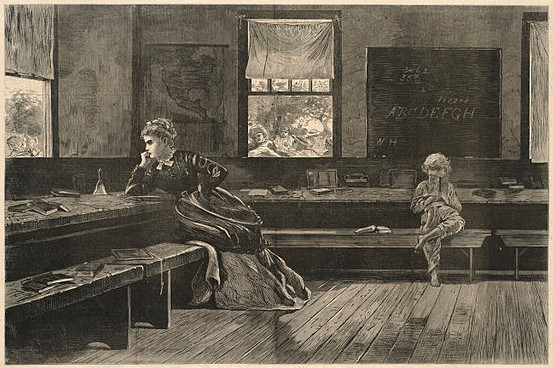

pensum

n. a piece of schoolwork imposed as a punishment

asmatographer

n. a composer of songs

While on the road with his 1927 musical Funny Face, George Gershwin left “two notebooks containing at least forty tunes” in a hotel room in Wilmington, Del. “After calling the hotel and learning the notebooks could not be located, he did not seem greatly perturbed,” wrote his brother and lyricist, Ira. “His attitude is that he can always write new ones.”

George was a songwriting machine, always at work. “I can think of no more nerve-wracking, no more mentally arduous task than making music,” he said in 1930. “There are times when a phrase of music will cost many hours of internal sweating.” Though he would sometimes try ideas at the piano, he insisted that “the actual composition must be done in the brain” — the fifth and final version of “Strike Up the Band” came to him in bed, and he heard, and even saw on paper, the complete construction of Rhapsody in Blue while riding a train from New York to Boston. “Like a pugilist,” he once said, “the songwriter must always keep in training.”

Ira’s struggle was less apparent. While working on lyrics he would wander the room, singing to himself or playing the piano with one finger. A new maid once asked his wife, “Don’t Mr. Gershwin never go to work?”

tongue-shot

n. speaking or talking distance, voice-range

Inhabitants of La Gomera, a small mountainous island in the Canary group, use a whistled language called the Silbo to communicate over great distances. “This is a form of telephony inferior to ours as regards range, but superior to it in so far as the only apparatus required is a sound set of teeth and a good pair of lungs,” noted Glasgow University phoneticist André Classe in New Scientist in 1958. “The normal carrying power is up to about four kilometres when conditions are good, over twice as much in the case of an exceptional whistler operating under the most favourable circumstances.”

greenswardsmanship

n. the cultivation of an unusually and enviably excellent lawn

haliography

n. a description of the sea

Charles Dickens’ 1850 novel David Copperfield climaxes with a dramatic tempest at Yarmouth:

The tremendous sea itself, when I could find sufficient pause to look at it, in the agitation of the blinding wind, the flying stones and sand, and the awful noise, confounded me. As the high watery walls came rolling in, and, at their highest, tumbled into surf, they looked as if the least would engulf the town. As the receding wave swept back with a hoarse roar, it seemed to scoop out deep caves in the beach, as if its purpose were to undermine the earth. When some white-headed billows thundered on, and dashed themselves to pieces before they reached the land, every fragment of the late whole seemed possessed by the full might of its wrath, rushing to be gathered to the composition of another monster. Undulating hills were changed to valleys, undulating valleys (with a solitary storm-bird sometimes skimming through them) were lifted up to hills; masses of water shivered and shook the beach with a booming sound; every shape tumultuously rolled on, as soon as made, to change its shape and place, and beat another shape and place away; the ideal shore on the horizon, with its towers and buildings, rose and fell; the clouds fell fast and thick; I seemed to see a rending and upheaving of all nature.

Tolstoy wrote, “If you sift the world’s prose literature, Dickens will remain; sift Dickens, David Copperfield will remain; sift David Copperfield, the description of the storm at sea will remain.” The scene formed the conclusion of Dickens’ public readings from the novel, and was often hailed as the grandest moment in his performances. Thackeray’s daughter Annie said the storm scene was more thrilling than anything she had ever seen in a theater: “It was not acting, it was not music, nor harmony of sound and color, and yet I still have an impression of all these things as I think of that occasion.”