fustigate

v. to strike with a cudgel

fustigate

v. to strike with a cudgel

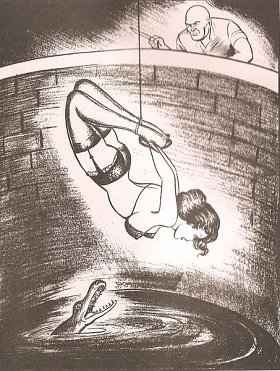

noyade

n. a mass execution by drowning

conclamant

adj. crying out together

commorient

adj. dying together or at the same time

J.M.W. Turner’s 1840 painting The Slave Ship recalls a brutal convention in the Atlantic slave trade — an insurance company would reimburse a captain for a slave who was lost at sea, but not for one who died of illness aboard ship. In 1781 Luke Collingwood, captain of the Zong, threw 133 sick and malnourished Africans overboard so that he could claim their value from his insurers. Turner displayed the painting next to lines from his own poem:

Aloft all hands, strike the top-masts and belay;

Yon angry setting sun and fierce-edged clouds

Declare the Typhon’s coming.

Before it sweeps your decks, throw overboard

The dead and dying — ne’er heed their chains

Hope, Hope, fallacious Hope!

Where is thy market now?

Britain had already outlawed its own slave trade when the painting appeared, but its impact encouraged the empire to oppose the institution everywhere.

filipendulous

adj. hanging by a thread

A cube suspended by a corner casts a hexagonal shadow.

periclitate

v. to endanger

omnilegent

adj. having read everything

cagamosis

n. marital unhappiness

anserine

adj. of or resembling a goose

In 1936, Polish mathematician Stanislaw Mazur offered a live goose to the first person who could determine whether every Banach space has a Schauder basis. Thirty-seven years later, his Swedish colleague Per Enflo claimed the prize. The ceremony was broadcast throughout Poland. (Thanks, Jeremy.)

In the public gardens at Halifax, there is an eccentric goose that seems to manifest a genuine affection. Whenever a certain old gentleman, whose name we do not know, approaches the pond and calls ‘Bobby,’ the goose will leave the pond and sit beside him, and when he leaves to go home, will follow close at his feet, like a dog, to the gate, and sometimes into the street, when it has to be forcibly put back, to its manifest disgust, for it goes off to its native element twisting its tail with indignation, and giving vent to sundry discordant squeaks. The old gentleman says he has never fed it, or petted it in any way, which makes it more remarkable; but we are told by a frequenter of the gardens that about two or three years ago a man used to come there and feed this identical goose regularly, so we are inclined to think that it is a case of mistaken identity on the part of his gooseship. Anyway, it is an interesting question for ornithologists to solve, whether geese (supposed to be the most stupid of birds) have memory and can experience the sensation of gratitude.

— James Baird McClure, ed., Entertaining Anecdotes From Every Available Source, 1879

evancalous

adj. pleasant to embrace

clipsome

adj. fit to be embraced

sgiomlaireachd

n. (Scottish Gaelic) the habit of dropping in at mealtimes

cunctator

n. a procrastinator