afterwit

n. knowledge gained too late to do any good

Search Results for: in a word

In a Word

jentacular

adj. pertaining to breakfast

In a Word

hadeharia

n. constant use of the word “hell”

In a Word

wittol

n. a man who knows of and tolerates his wife’s infidelity

Last Words

In The King’s English (1997), Kingsley Amis cites an old joke that illustrates the confusing distinction between shall and will:

A swimmer in difficulties was heard to shout, ‘I will drown and nobody shall save me.’ At an inquest on the unfortunate fellow, English jurors wanted a verdict of suicide, Scottish jurors a verdict of death by misadventure, and MacTavish pressed for a rider or footnote rebuking witnesses for making no effort to rescue the victim.

Under the old rule, I shall indicated a prediction and I will denoted a promise or threat. Confusingly, in the second and third persons these meanings were reversed, so that you/she will indicated simple futurity and you/she shall denoted an intention or command. Still more confusingly, old-fashioned speakers of Scottish English reversed this whole understanding of the matter. So while the English jurors thought the swimmer was saying, “It is my intention to drown, and it is my express desire that nobody try to save me,” the Scots took him to say, “I am going to drown and it seems that nobody is going to save me.”

All this has only grown more confused with the popularity of contractions such as I’ll and you’ll, and Americans have generally dispensed with shall and use will for everything. Of the joke, Amis writes, “Nobody tells that one today.”

Overspecialized Words

Some words become famous for their implausibly specific definitions:

ucalegon: a neighbor whose house is on fire

nosarian: one who argues that there is no limit to the possible largeness of a nose

undoctor: to make unlike a doctor

Mrs. Byrne’s Dictionary of Unusual, Obscure, and Preposterous Words, by Josefa Heifetz Byrne, collects examples ranging from atpatruus (“a great-grandfather’s grandfather’s brother”) to zumbooruk (“a small cannon fired from the back of a camel”). My own favorite is groak, “to watch people silently while they’re eating, hoping they will ask you to join them.”

Alas, most of these don’t appear in the magisterial Oxford English Dictionary. Accordingly, in 1981 Jeff Grant burrowed his way into the OED in a deliberate search for obscure words. When he reached the end of A he sent his 10 favorite finds to the British magazine Logophile:

acersecomic: one whose hair was never cut

acroteriasm: the act of cutting off the extreme parts of the body, when putrefied, with a saw

alerion: an eagle without beak or feet

all-flower-water: cow’s urine, as a remedy

ambilevous: left-handed on both sides

amphisbaenous: walking equally in opposite directions

andabatarian: struggling while blindfolded

anemocracy: government by wind

artolatry: the worship of bread

autocoprophagous: eating one’s own dung

“I have been working slowly through ‘B’ and so far my favourite is definitely ‘bangstry’, defined as ‘masterful violence’, an obsolete term that is surely overdue for a comeback.”

(From Word Ways, November 1981.)

Late Word

A week after songwriter Jim Croce died in a plane crash in 1973, his wife, Ingrid Jacobson, received this letter:

Dear Ing,

I know I haven’t been very nice to you for some time, but I thought it might be of some comfort, Sweet Thing, to understand that you haven’t been the only recipient of JC’s manipulations. But since you can’t hear me and can’t see me, I can’t bullshit, using my sneaky logic and facial movements. I have to write it all down instead, which is lots more permanent. So it can be re-read instead of re-membered, so, it’s really right on the line.

I know that you see me for who I am, or should I say, as who I are. ‘Cause I’ve been lots of people. If Medusa had personalities or attitudes instead of snakes for her features, her name would have been Jim Croce. But that’s unfair to you and it’s also unhealthy for me. And I now want to be the oldest man around, a man with a face full of wrinkles and lots of wisdom.

So this is a birth note, Baby. And when I get back everything will be different. We’re gonna have a life together, Ing, I promise. I’m gonna concentrate on my health. I’m gonna become a public hermit. I’m gonna get my Master’s Degree. I’m gonna write short stories and movie scripts. Who knows, I might even get a tan.

Give a kiss to my little man and tell him Daddy loves him.Remember, it’s the first sixty years that count and I’ve got 30 to go.

I Love you,

Jim

(From Ingrid’s 2012 memoir, I Got a Name: The Jim Croce Story.)

In Other Words

Lexicon Recentis Latinitas, published by the Vatican, invents Latin versions of modern words and phrases, so students can refer to items that didn’t exist in the ancient world:

bestseller: liber maxime divenditus

car wash: autocinetorum lavatrix

Christmas tree: arbor natalicia

disc brakes: sufflamen disci forma

dishwasher: escariorum lavator

to flirt: lusorie amare

leased property: locatio in emptionem convertibilis

pinball machine: sphaeriludium electricum nomismate actum

refrigerator: cella frigorifera

to slack off on the job: neglegenter operor

television: instrumentum televisificum

traffic jam: fluxus interclusio

washing machine: machina linteorum lavatoria

These examples are from a selection published in 1991 in Harper’s, which said that 75 percent of the 18,000 entries in that year’s edition were terms that had never had Latin equivalents. I can’t find the whole book, but the Vatican website offers an Italian-Latin glossary with some entries in English (hot pants are brevíssimae bracae femíneae).

In Other Words

In the 19th century, British polymath William Barnes tried to reform English by limiting it to words of Saxon-English origin. Where no “Teutonic” words were available to express his meaning, he made up alternatives, such as sky-sill for horizon, glee-craft for music, wort-lore for botany, hearsomeness for obedience, somely for plural, and folkwain for omnibus.

In 1948, Richard Lister challenged the readers of the New Statesman to write the opening paragraphs of a novel set in present-day London in this style of reformed English. Reader D.M. Low offered this:

As Ernest was wafted up on the dredger from the thorough-hole at Kingsway he was inwardly upborne to see Pearl again; but, alas, evenly castdown for the blue-eyed bebrilled booklearner was floating downwards on the other ladderway. It was now or never. Ernest fought back against the rising stairs and the gainbuildfulness of hirelings bound for work. Pushing aside fingerwriters, shophelpers and even deeded reckoning-keepers, by an overmanly try he reached the bottom eventimeously with Pearl.

‘What luck! Can you eat with me tonight? I know a fair little upstaker near here.’

‘Oh! I can’t. My Between-go is in Fogmonth, and I must get through and …’

The rumble of the ambercrafty wagonsnake drowned her words.

‘Hark! There’s the tug. I must fly.’

It was hard to be wisdomlustful. Forlorn in his trystlessness Ernest sought Kingsway again and dodging hire-shiners and other self-shifters recklessly headed towards the worldheadtownly manystreakiness of the Strand.

He appended this glossary:

dredger: escalator.

ladderway: escalator.

upborne: elated.

evenly: equally.

bebrilled: bespectacled, (German Brille).

booklearner: student.

gainbuildfulness: obstructiveness.

fingerwriters: typists, cf. dattilografa.

deeded reckoning keepers: chartered accountants.

overmanly: superhuman.

eventimeously: simultaneously.

upstaker (less correctly upstoker): restaurant.

Between go: student slang for Between while try out i.e., Intermediate Examination.

Fogmonth: November.

ambercrafty: electric, lit. electric powered.

wagonsnake: train (archaic and poet.).

tug: train cf. German Zug.

wisdomlustful: philosophical.

trystlessness: disappointment.

hire-shiners: taxis.

self-shifters: automobiles.

manystreakiness: variety.

worldheadtownly: cosmopolitan.

Other readers had suggested eyebiting for attractive, lip-hair for moustache, slidehorn for trombone, and smokeweed for cigarette. The winning entries are here.

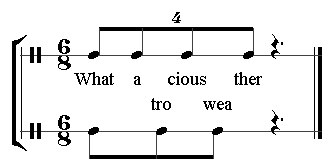

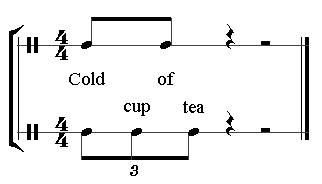

Words and Music

Wikimedia user Tarquin points out that the natural rhythm of spoken language can be used to teach polyrhythms.

Above: The phrase “cold cup of tea,” spoken naturally, approximates a rhythm of 2 against 3.

Below: The phrase “what atrocious weather” approximates 4 against 3.