In 2004, Canadian musician Andrew Huang wrote a song that encodes the first 101 digits of π.

Also: A “piku” is a haiku whose word lengths reflect the digits of π:

How I love a verse

Contrived to unhusk dryly

One image nutshell

In 2004, Canadian musician Andrew Huang wrote a song that encodes the first 101 digits of π.

Also: A “piku” is a haiku whose word lengths reflect the digits of π:

How I love a verse

Contrived to unhusk dryly

One image nutshell

University of Arizona anthropologist Keith Basso found that when the automobile was introduced into the reservation of the Western Apache of Arizona, they described it by applying their words for the human body:

| Anatomical Term | Extended Meaning |

| “shoulder” | “front fender(s)” |

| “hand+arm” | “front wheel(s), tire(s)” |

| “chin+jaw” | “front bumper” |

| “foot,” “feet” | “rear wheel(s), tire(s)” |

| “face” | “area extending from top of windshield to bumper” |

| “forehead” | “front portion of cab, or automobile top” |

| “nose” | “hood” |

| “back” | “bed of truck” |

| “hip+buttock” | “rear fender(s)” |

| “mouth” | “opening of pipe leading to gas-tank” |

| “eye(s)” | “headlight(s)” |

| “vein(s)” | “electrical wiring” |

| “entrails,” “guts” | “all machinery under hood” |

| “liver” | “battery” |

| “stomach” | “gas-tank” |

| “heart” | “distributor” |

| “lung” | “radiator” |

| “intestine(s)” | “radiator hose(s)” |

| “fat” | “grease” |

“When the automobile was introduced into Apache culture, it was perceived to possess a crucial defining attribute — the ability to move itself — which prompted its inclusion in the category labeled hinda [phenomena that are capable of generating and sustaining locomotive movement by themselves, such as man, quadrupeds, birds, reptiles, fish, insects, and some machines]. The traditional practice of describing the other members of this category with anatomical terms was then applied to automobiles, to produce the extended set described above.”

(Keith H. Basso, “Semantic Aspects of Linguistic Acculturation,” American Anthropologist, New Series 69:5 [October 1967], 471-477.)

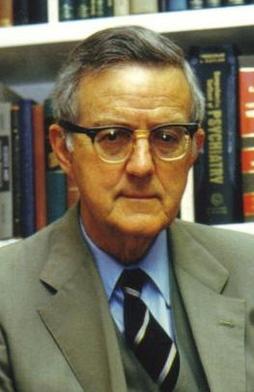

In 1967, Ian Stevenson closed a combination lock and placed it in a filing cabinet in the psychiatry department at the University of Virginia. He had set the combination using a word or phrase known only to himself. He told his colleagues that he would try to communicate the code to them after his death, as potential evidence that his awareness had survived.

The combination “is extremely meaningful to me,” he said. “I have no fear whatever of forgetting it on this side of the grave and, if I remember anything on the other side, I shall surely remember it.”

His colleague Emily Williams Kelly told the New York Times, “Presumably, if someone had a vivid dream about him, in which there seemed to be a word or a phrase that kept being repeated — I don’t quite know how it would work — if it seemed promising enough, we would try to open it using the combination suggested.”

Stevenson died in 2007. As of October 2014, the lock remained unopened.

Hit by shrapnel on April 16, 1917, French infantryman Jean-Louis Cros managed to scribble this message before dying:

My dear wife, my dear parents and all I love, I have been wounded. I hope it will be nothing. Care well for the children, my dear Lucie; Leopold will help you if I don’t get out of this. I have a crushed thigh and am all alone in a shell hole. I hope they will soon come to fetch me. My last thought is of you.

The card was sent to his family.

In August 1918 the Rev. Arthur Boyce found this letter on the battlefield near Rheims. The writer had asked the finder to forward it to his family:

My dear wife, I am dying on the battlefield. With my last strength God bless you and the kiddies. I am glad to give my life for my country. Don’t grieve over me — be proud of this fact. Goodbye and God bless you. Fred

When the kiddies get older tell them how I died.

He had written a similar note to his mother. His identity could not be discovered.

(From Peter Hart’s The Great War, 2013, and Richard van Emden’s The Quick and the Dead, 2012.)

Doubtful but entertaining:

Several sources define vacansopapurosophobia as “fear of blank paper” — it’s not in the Oxford English Dictionary, but it’s certainly a useful word.

I’ve also seen artiformologicalintactitudinarianisminist, “one who studies 4-5-letter Latin prefixes and suffixes.” I don’t have a source for that; it’s not in the OED either.

In Say It My Way, Willard R. Espy defines a cypripareuniaphile as “one who takes special pleasure in sexual intercourse with prostitutes” and acyanoblepsianite as “one who cannot distinguish the color blue.”

In By the Sword, his history of swordsmen, Richard Cohen defines tsujigiri as “to try out a new sword on a chance passerby.” Apparently that’s a real practice.

And one that is in the OED: mallemaroking is “the boisterous and drunken exchange of hospitality between sailors in extreme northern waters.”

(Thanks, Dave.)

Back in 2012 I mentioned that if A=1, B=2, C=3, etc., then ARM + BEND = ELBOW and KING + CHAIR = THRONE.

Peter Dawyndt of Ghent University challenged his students to come up with more, and they found these:

WHITE (65) + HOUSE (68) = GOVERNMENT (133)

PETER (64) + PAN (31) = NEVERLAND (95)

COMIC (43) + BOOK (43) = FANTASY (86)

ABSENT (61) + MINDED (49) = FORGETFUL (110)

BLOOD (48) + BATH (31) = MASSACRE (79)

DRUG (50) + ADDICT (41) = STONER (91)

MICRO (58) + SOFT (60) = COMPUTING (118)

RED (27) + BULL (47) = COCKTAIL (74)

EGG (19) + PLANT (63) = AUBERGINE (82)

CUSTARD (86) + CREAM (40) = BISCUITRY (126)

VISUAL (84) + BASIC (34) = MICROSOFT (118)

ENERGY (74) + DRINK (56) = JAGERMEISTER (130)

MONA (43) + LISA (41) = LEONARDO (84)

DOWN (56) + LOAD (32) = ITUNES (88)

BLACK (29) + JACK (25) = VEGAS (54)

SUN (54) + RISE (51) = HORIZON (105)

POLICE (60) + CAR (22) = PATROL (82)

CHURCH (61) + MAN (28) = RELIGION (89)

FAMILY (66) + TREE (48) = ANCESTORS (114)

HAND (27) + GUN (42) = MAGNUM (69)

RAIN (42) + BOW (40) = COLORS (82)

ANT (35) + LION (50) = DOODLEBUG (85)

BOTTOM (85) + LINE (40) = CONCLUSION (125)

BACK (17) + SLASH (59) = HYPHEN (76)

BILL (35) + FOLD (37) = MONEY (72)

URBAN (56) + LEGEND (47) = BULLSHIT (103)

CALL (28) + GIRL (46) = HARLOT (74)

STAR (58) + TREK (54) = VOYAGERS (112)

Names of famous people:

JOHN (47) + CLEESE (49) = HUMOUR (96)

TOM (48) + HANKS (53) = FORREST (101)

BOB (19) + MARLEY (74) = RASTAFARI (93)

KURT (70) + COBAIN (44) = NOVOSELIC (114)

NELSON (79) + MANDELA (50) = HUMANITARIAN (129)

EMMA (32) + WATSON (92) = VOLDEMORT (124)

JAMES (48) + BOND (35) = DANIEL (45) + CRAIG (38)

GEORGE (57) + LUCAS (56) = JAR (29) + JAR (29) + BINKS (55)

STEPHEN (87) + HAWKING (73) = TEXT (69) + TO (35) + SPEECH (56)

CLOCKWORK (111) + ORANGE (60) = STANLEY (96) + KUBRICK (75)

(Thanks, Peter.)

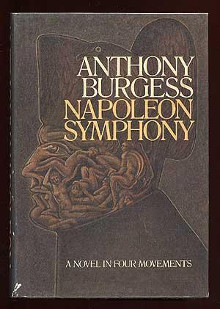

Anthony Burgess based his 1974 novel Napoleon Symphony explicitly on the structure of Beethoven’s Symphony No. 3, the Eroica:

There he lies,

Ensanguinated tyrant

O bloody, bloody tyrant

See

How the sin within

Doth incarnadine

His skin

From the shin to the chin.

Overall, Burgess said, he wanted to pursue “one mad idea”: “to give / Symphonic shape to verbal narrative” and to “impose on life … the abstract patterns of the symphonist.”

He dedicated the novel to Stanley Kubrick, hoping that it might form the basis of the director’s long-planned biography of the emperor, but Kubrick decided that “the [manuscript] is not a work that can help me make a film about the life of Napoleon.” Undismayed, Burgess developed it instead into an experimental novel. The critics didn’t like it, but he said it was “elephantine fun” to write.

(From Theodore Ziolkowski, Music Into Fiction, 2017.)

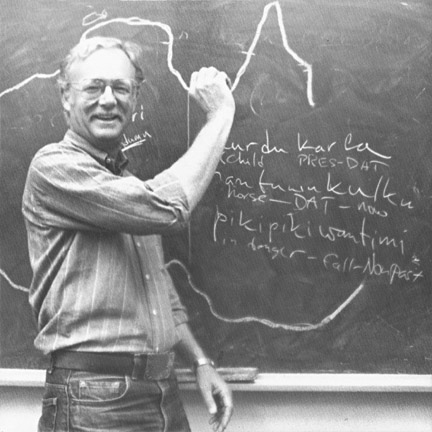

Linguist Ken Hale had a preternatural ability to learn new languages. “It was as if the linguistic faculty which normally shuts off in human beings at the age of 12 just never shut off in him,” said his MIT colleague Samuel Jay Keyser.

“It’s more like a musical talent than anything else,” Hale told The New York Times in 1997. “When I found out I could speak Navajo at the age of 12, I used to go out every day and sit on a rock and talk Navajo to myself.” Acquiring new languages became a lifelong obsession:

In Spain he learnt Basque; in Ireland he spoke Gaelic so convincingly that an immigration officer asked if he knew English. He apologised to the Dutch for taking a whole week to master their somewhat complex language. He picked up the rudiments of Japanese after watching a Japanese film with subtitles.

He estimated that he could learn the essentials of a new language in 10 or 15 minutes, well enough to make himself understood, if he could talk to a native speaker (he said he could never learn a language in a classroom). He would start with parts of the body, he said, then animals and common objects. Once he’d learned the nouns he could start to make sentences and master sounds, writing everything down.

He devoted much of his time to studying vanishing languages around the world. He labored to revitalize the language of the Wampanoag in New England and visited Nicaragua to train linguists in four indigenous languages. In 2001 his son Ezra delivered his eulogy in Warlpiri, an Australian aboriginal language that his father had raised his sons to speak. “The problem,” Ken once told Philip Khoury, “is that many of the languages I’ve learned are extinct, or close to extinction, and I have no one to speak them with.”

“Ken viewed languages as if they were works of art,” recalled another MIT colleague, Samuel Jay Keyser. “Every person who spoke a language was a curator of a masterpiece.”

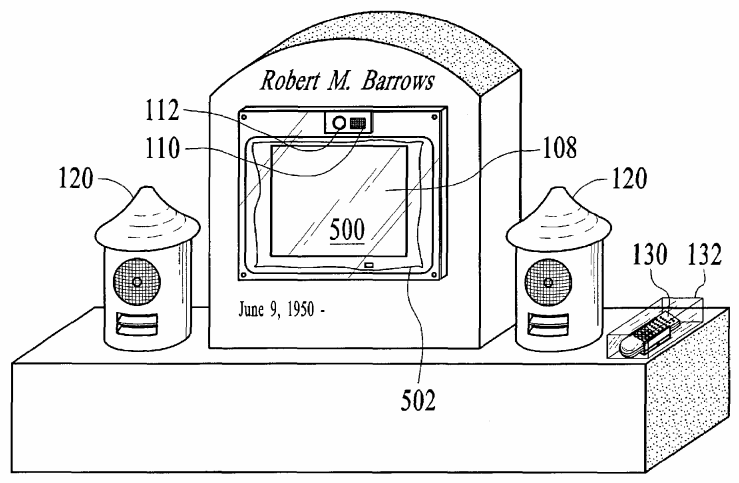

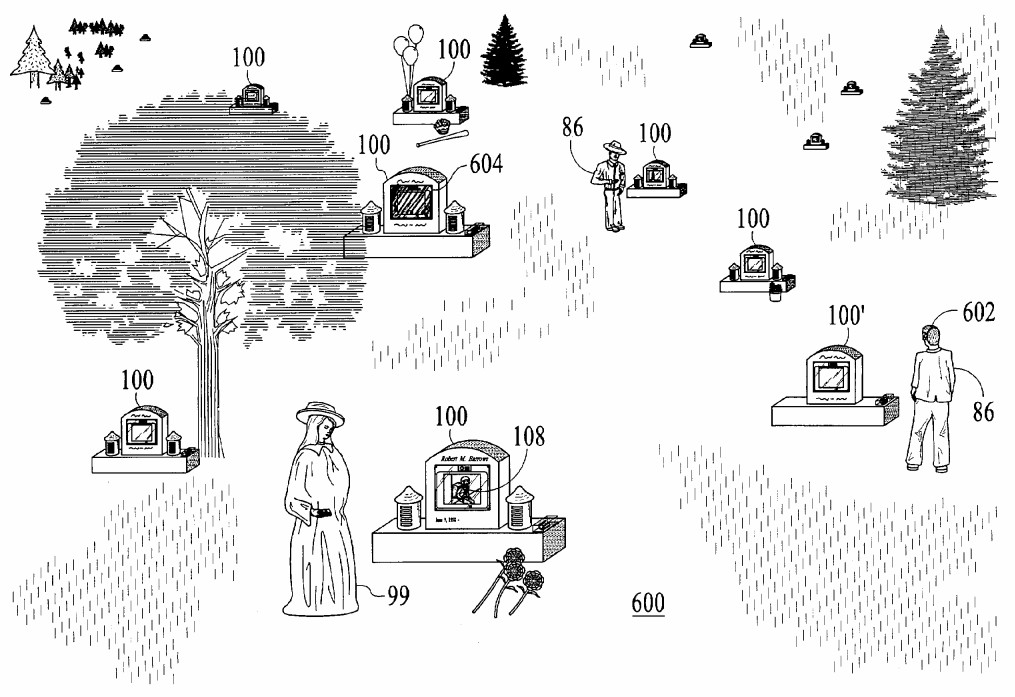

Inventor Robert Barrows thought up a high-tech memorial in 2005: a hollowed-out headstone equipped with a weatherproofed computer monitor.

“I envision being able to walk through a cemetery using a remote control, clicking on graves and what all the people buried there have to say,” he told the Wall Street Journal. “They can say all the things they didn’t have the opportunity or guts to say when they were alive.”

He estimated that a “video-enhanced grave marker” might add $4,000 to the cost of a high-end $4,000 tombstone. If they really take off we’ll need wireless headsets to keep down the racket at the cemetery:

05/09/2017 They’re already doing this in Slovenia. (Thanks, Dan.)