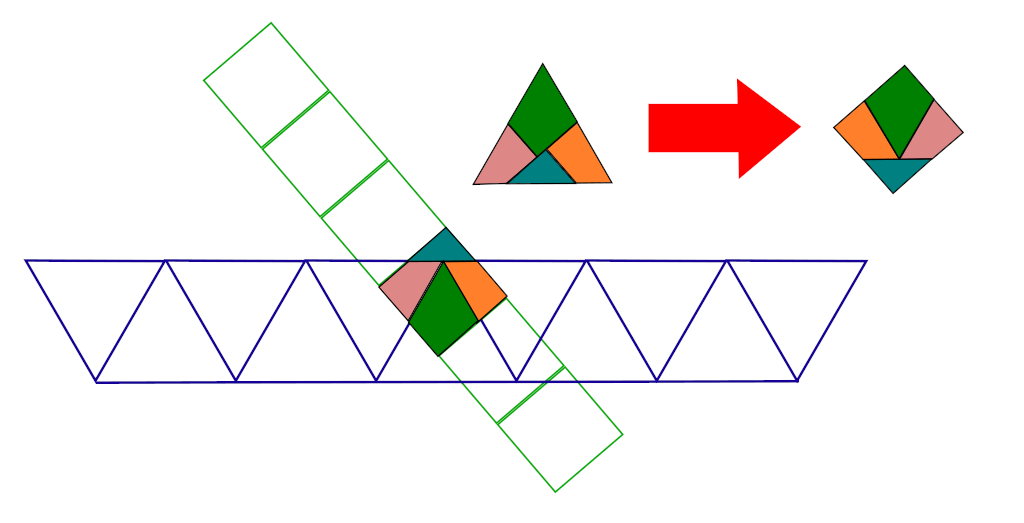

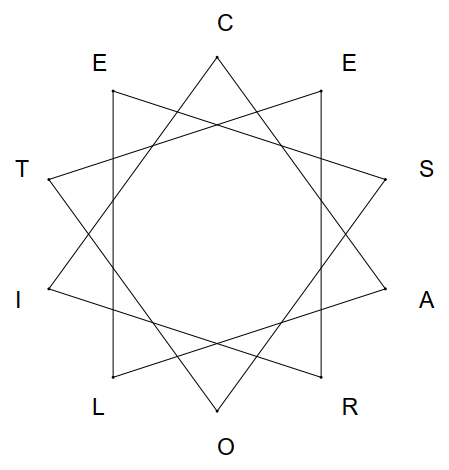

Write the word CESAROLITE in a circle and then trace out the letters in its anagram ESOTERICAL — the result is a perfect 10-pointed star:

Only 5.7 percent of anagrams in English are “maximally shuffled,” meaning that no letter retains its original neighbors. And even those rarely produce such pleasing symmetry when they’re diagramed like this. This is the largest “perfect” star anagram found in a systematic search by Jason Parker and Dan Barker; for more, see the link below.

(Jason Parker and Dan Barker, “Star Anagram Detection and Classification,” Recreational Mathematics Magazine 12:20 [June 2025], 19-40.)