- In the King James Bible, Ezra 7:21 lacks only the letter J, and 1 Chronicles 12:40 lacks only Q.

- In 2016 Pharmacy Times judged talimogene laherparepvec the hardest drug name to pronounce.

- 34 × 72 × 875 = 3472875 (B.J. van der Zwaag)

- The Estonian word kuulilennuteetunneliluuk (“bullet tunnel hatch”) is a palindrome.

- “No one ever forgets where he buried the hatchet.” — Kin Hubbard

Search Results for: in a word

Sharp Dealing

An episode from P.T. Barnum’s childhood in Bethel, Connecticut:

‘What is the price of razor strops?’ inquired my grandfather of a peddler, whose wagon, loaded with Yankee notions, stood in front of our store.

‘A dollar each for Pomeroy’s strops,’ responded the itinerant merchant.

‘A dollar apiece!’ exclaimed my grandfather; ‘they’ll be sold for half the money before the year is out.’

‘If one of Pomeroy’s strops is sold for fifty cents within a year, I’ll make you a present of one,’ replied the peddler.

‘I’ll purchase one on those conditions. Now, Ben, I call you to witness the contract,’ said my grandfather, addressing himself to Esquire Hoyt.

‘All right,’ responded Ben.

‘Yes,’ said the peddler, ‘I’ll do as I say, and there’s no backout to me.’

My grandfather took the strop, and put it in his side coat pocket.

Presently drawing it out, and turning to Esquire Hoyt, he said, ‘Ben, I don’t much like this strop now I have bought it. How much will you give for it?’

‘Well, I guess, seeing it’s you, I’ll give fifty cents,’ drawled the ‘Squire, with a wicked twinkle in his eye, which said that the strop and the peddler were both incontinently sold.

‘You can take it. I guess I’ll get along with my old one a spell longer,’ said my grandfather, giving the peddler a knowing look.

The strop changed hands, and the peddler exclaimed, ‘I acknowledge, gentlemen; what’s to pay?’

‘Treat the company, and confess you are taken in, or else give me a strop,’ replied my grandfather.

‘I never will confess nor treat,’ said the peddler, ‘but I’ll give you a strop for your wit;’ and suiting the action to the word, he handed a second strop to his customer. A hearty laugh ensued, in which the peddler joined.

‘Some pretty sharp fellows here in Bethel,’ said a bystander, addressing the peddler.

‘Tolerable, but nothing to brag of,’ replied the peddler; ‘I have made seventy-five cents by the operation.’

‘How is that?’ was the inquiry.

‘I have received a dollar for two strops which cost me only twelve and a half cents each,’ replied the peddler; ‘but having heard of the cute tricks of the Bethel chaps, I thought I would look out for them and fix my prices accordingly. I generally sell these strops at twenty-five cents each, but, gentlemen, if you want any more at fifty cents apiece, I shall be happy to supply your whole village.’

Our neighbors laughed out of the other side of their mouths, but no more strops were purchased.

(From his 1855 autobiography.)

Excerpts

J. Bryan III used to challenge his friends to think of an English word that contains either of the following strings of letters:

ILIL

ILIW

“I’ve never played the game with anyone who could solve either of these combinations.” Can you?

C Change

How can we make sense of this passage, composed by Willard R. Espy?

The Optic Reed has a Haste Harm. It Hose, one assumes, not to be Lever; it neither Heats the Ripple, nor Hides the Razed sinner for his Rude Rime; it is not Old. Then Leave to it; ere thy grave Loses, thou mayst find here the Hart to the Rest thou Ravest to Limb.

Place Settings

In his 1954 book Language in Relation to a Unified Theory of the Structure of Human Behavior, Kenneth Pike presents a toy language in which meaning is determined by the relative order of the elements. If these expressions have the indicated meanings:

1. los "It is smoke"

2. mif "It is a ball"

3. kap "They are eyes"

4. losmif "The ball is smoking"

5. miflos "The smoke is rolling"

6. mifmif "The ball is rolling"

7. mifmiflos "The smoke is rolling in round puffs"

8. mifmifkap "He is rolling his eyes around" or

"The eyes are rolling around"

9. losmifkap "His eyes roam darkly"

10. mifkaplos "The smoke is trying to escape" or

"The smoke looks around"

11. kapmifmif "I can see the ball rolling"

12. mifkapkap "He is looking around"

13. losloskap "His eyes are smoldering menacingly"

… what would be meant by kapmiflos and kapkapkap?

All Sides

“Conjugated nouns,” offered by Ohio State University linguist Arnold M. Zwicky in Verbatim in 1975:

I steal the keel. I stole the coal. I have stolen the colon.

They choose the hues. They chose the hose. They have chosen the hosen.

They mow the banks of the row. They mowed the banks of the road. They have mown the banks of the Rhone.

I do it with the buoys. I did it with the biddies. I have done it with the bunnies.

Mike Anglin took this up in Word Ways in 1988:

I tear the hair; I tore the whore; I have torn the horn.

I see the sea; I saw the saw; I have seen the scene.

I draw the law; I drew the loo; I have drawn the lawn.

I throw the bow; I threw the boo; I have thrown the bone.

I sink the mink; I sank the manque; I have sunk the monk.

I choose the booze; I chose the bows; I have chosen the bosun.

I weave the leaves; I wove the loaves; I have woven the love-ins.

I forsake the cake; I forsook the cook; I have forsaken the whole mess.

Philip M. Cohen added, “I scare for the mare; I score for the more; I have scorn for the morn.”

Mnemonics

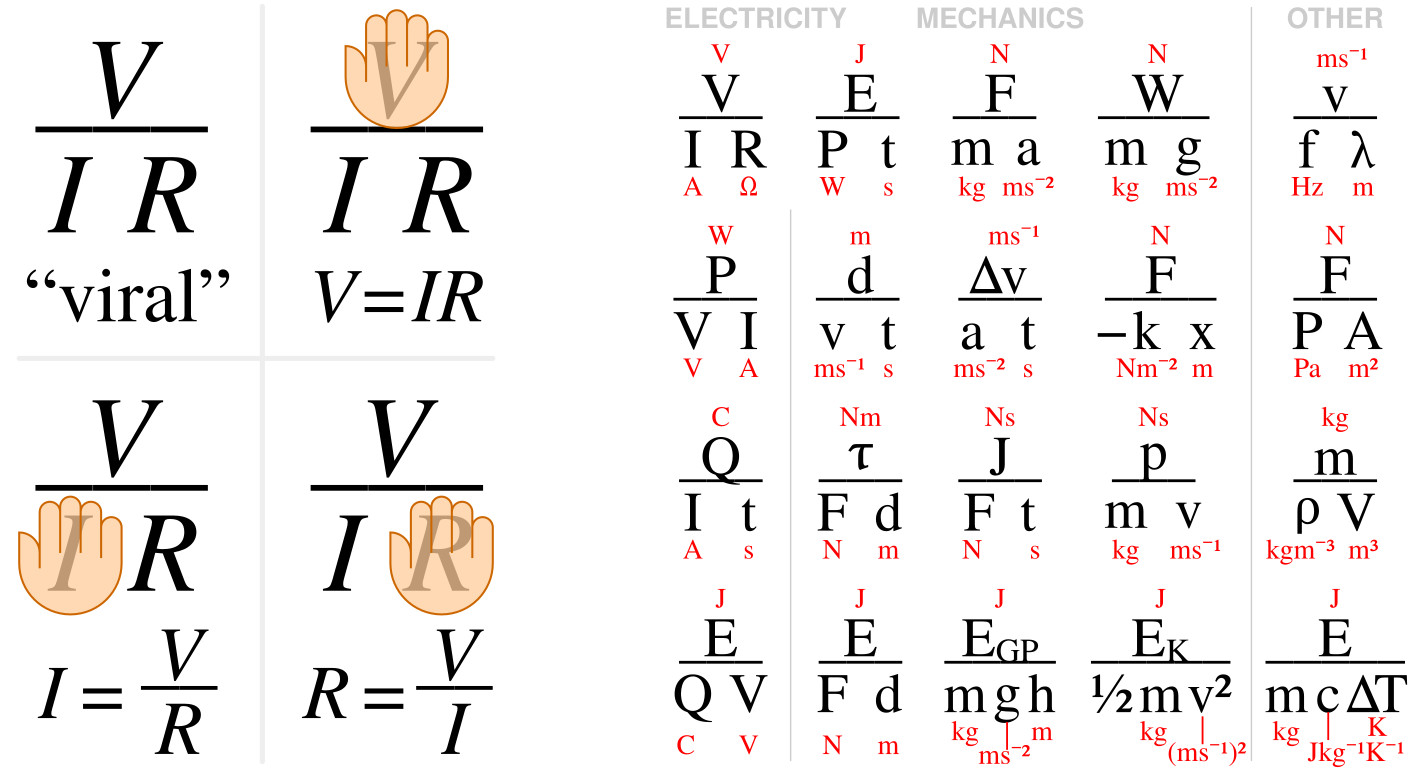

Ohm’s law states that V = IR, where V is the voltage measured across a conductor, I is the current through the conductor, and R is the conductor’s resistance. In the image mnemonic at left (easily remembered by the word “viral”), covering any of the unknowns gives the formula in terms of the remaining parameters: V = IR, I = V/R, R = V/I.

Wikimedia user CMG Lee has devised other mnemonics in the same style for high-school physics students (right). For example, F = ma, m = F/a, a = F/m. In the corresponding SVG file you can hover over a symbol to see its meaning and formula.

Apt

Writing in the Wall Street Journal about long sentences in literature, Laurie Winer offered her thoughts in a single sentence of 854 words:

In order to credit William Faulkner — as the Guinness Book of World Records does — with the longest sentence in literature, one must include, when counting the words in Faulkner’s erratically punctuated, loosely defined ‘sentences,’ lengthy italicized passages that echo what passes through a character’s mind; not to mention parentheses within parentheses; and long sentences connected to sentence fragments by dashes where periods, strictly speaking, should be; as well as run-on paragraphs that begin audaciously with a lower-case letter; and, while Guinness says the longest sentence is a 1,300-word tirade in Absalom, Absalom! there is, by liberal Faulknerian standards, a 1,928-word sentence (beginning ‘They both bore it as though in deliberate flagellant exaltation’) in that book which contains a 1,360-word parenthetical memory/thought that has within it at least 32 traditional sentences; so perhaps Faulkner should not be holding this title after all (from his London office a Guinness editor, Colin Smith, who says he has never seen Absalom, Absalom!, names as his source for the longest sentence entry the 1945 Bookmen’s Bedlam of Literary Oddities, a fustian collection of curiosa by bibliophile Walter Hart Blumenthal, which doesn’t mention Faulkner at all and instead gives the palm for sequential verbosity to Edward Phillips’s Preface to Theatrum Poetarium, written in 1675, for a 1,012-word sentence) even though others, including the writer Malcolm Cowley, cite another Faulkner sentence, found in the story ‘The Bear,’ as among the longest ever written; viz., in his introduction to the story in the 1946 The Portable Faulkner, Mr. Cowley calls this whopper, which begins ‘To him it was as though the ledgers in their scarred cracked leather bindings,’ a 1,800-word sentence when in fact it is, by the most liberal definition, a 1,600-word Faulknerian sentence, which is, under closer scrutiny, a 91-word sentence with no period followed by a new paragraph (indented) beginning with a lower-case letter that contains nothing but a 67-word sentence fragment that is followed by another paragraph fragment, etc. (even Albert Erskine, Faulkner’s editor at Random House, says of the long word group in ‘The Bear’: ‘New sentences begin whether the author puts a period there or not’), which may sound petty, but, if you’re going to call something the longest sentence, the term sentence must have some meaning or else what’s the point of bestowing the title (you may believe, as a confident New York City librarian told me, that the longest sentence in literature is the last 40,000 words of James Joyce’s Ulysses, which does contain two periods but which is really a poem, a chant, or free association that disintegrates at times to a point where it is unrecognisable as formal grammar or even as English (‘… I can see his face clean shaven Frseeeeeeeeeeeeeeeeeeeeefrong that train …’) and clings only, as the critic Roy K. Gottfried points out, to a morphemic structure, though while Joyce broke ground and freed his prose from the tyranny of syntax, he did not write a 40,000-word sentence) unless you give it to someone who actually wrote an extremely long sentence, as Marcel Proust did in his seven-volume masterpiece (first published as eight volumes, though Bookmen’s Bedlam calls it eleven and another reference book, Felton & Fowler’s Best, Worst, and Most Unusual, remembers it as sixteen — these record books seem to get none of the numbers right) Remembrance of Things Past, which contains in it a famous, perfect 958-word (in the C.K. Scott Moncrieff translation) sentence (it begins ‘Their honour precarious, their liberty provisional …’) that appears near the start of the fourth book, Sodome et Gomorrhe or, as it is known in English, Cities of the Plain, just after the narrator has witnessed a homosexual encounter between Jupien the tailor and the Baron de Charlus, an encounter that initiates a rumination on the part of our young hero, whose creator was himself a half-Jewish homosexual, on the tenuous situation of the homosexual in society and on how he is like the Jew in respect to the duplicity of his life, seeking to assimilate and yet compelled to remain different, permeated with the pain of the ever-present knowledge that, because of what he is, he gives cause to others to snub him, alienate him, or hate him, and of how this difference, shared by members on the highest and lowest rungs of society, bonds the ambassador to the felon, or the prince to the ruffian, for here is a sentence that does not suffocate the reader with its verbiage (as might the work of certain Teutotonic runners-up for the longest sentence, such as Thomas Bernhard or Hermann Broch); here is a sentence whose length befits its subject matter and its context in the whole; here is a sentence that can be parsed; here is a sentence that should be called the longest in literature (taking into account the possibility that there exist longer grammatical sentences — maybe some crank somewhere wrote a one-sentence book — but we are biased in favor of our titleholder’s also being a genius) by the Guinness people; so we suggest they change their Faulkner entry.

She followed this with a one-word paragraph: “Now.”

(Via Willard R. Espy’s The Word’s Gotten Out, 1989.)

All Together Now

In March 1985, Science Digest published four pangrams composed by its readers — each 26-letter sentence uses every letter in the English alphabet:

Shiv cwm lynx, fjord qutb, zap keg. (Randall Kryn) “A powerful Islamic saint (qutb) who lives in a fjord is told first to knife a troublesome lynx that lives in a mountain hollow (cwm) and then to celebrate by awesomely attacking a keg of brew.”

Schwyz fjord map vext Qung bilk. (Brian Phillips) “A cheat (bilk) from the Qung tribe in southern Africa could not understand a map of fjords in Schwyz, a canton of Switzerland.”

Fly vext bird; zag cwm’s qoph junk! (Kent Teufel) “A blimp explodes, shattering a sign in Hebrew. Pieces of qoph, the nineteenth letter of the Hebrew alphabet, fall into a cwm. An annoyed, low-flying bird is told to zag in order to avoid the falling pieces.”

Qoph’s jag biz vext drunk cwm fly. (Falko Schilling) “The business of making the sharp notched edge on the nineteenth letter of the Hebrew alphabet irritated the inebriated fly from the mountain hollow.”

All the words appear in Webster’s Third New International Dictionary.

Last November, the National Security Agency published five pangram crosswords — in each completed grid, every letter of the alphabet must appear once.

Zoology

Reponse of a 10-year-old child invited to write an essay about a bird and a beast:

The bird that I am going to write about is the owl. The owl cannot see at all by day and at night is as blind as a bat.

I do not know much about the owl, so I will go on to the beast which I am going to choose. It is the cow. The cow is a mammal. It has six sides — right, left, an upper and below. At the back it has a tail on which hangs a brush. With this it sends the flies away so that they do not fall into the milk. The head is for the purpose of growing horns and so that the mouth can be somewhere. The horns are to butt with, and the mouth is to moo with. Under the cow hangs the milk. It is arranged for milking. When people milk, the milk comes and there is never an end to the supply. How the cow does it I have not yet realised, but it makes more and more. The cow has a fine sense of smell; one can smell it far away. This is the reason for the fresh air in the country.

The man cow is called an ox. It is not a mammal. The cow does not eat much, but what it eats it eats twice, so that it gets enough. When it is hungry it moos, and when it says nothing it is because its inside is all full up with grass.

— Ernest Gowers and Sir Bruce Fraser, The Complete Plain Words, 1973