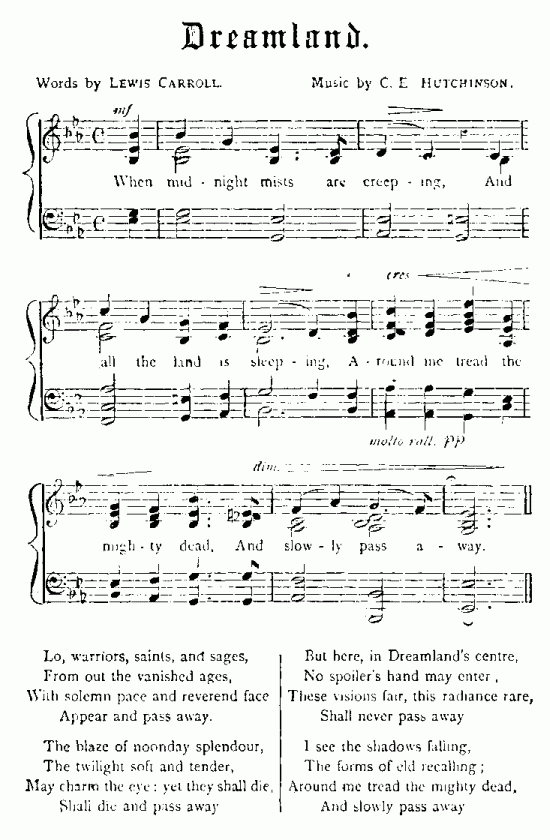

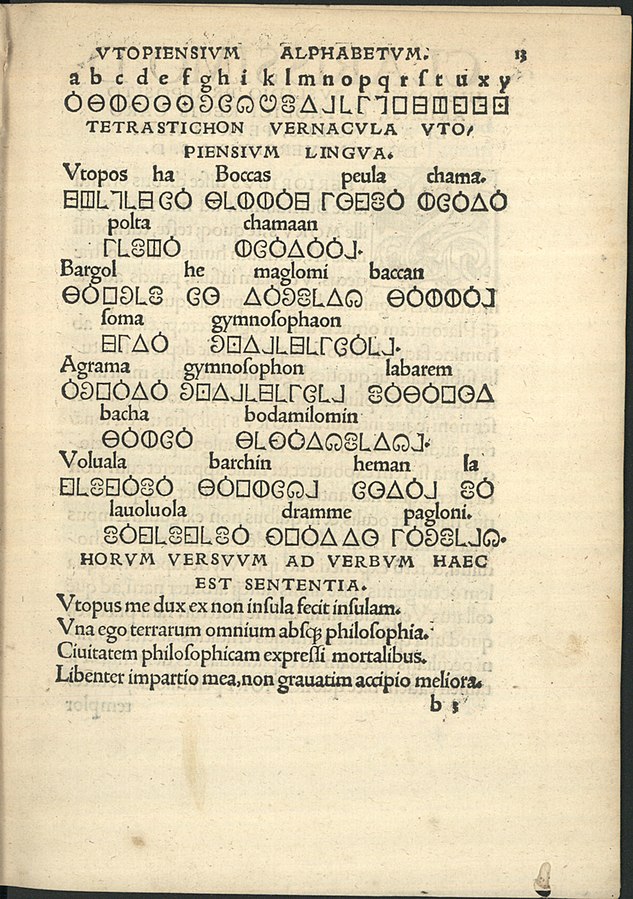

Thomas More’s Utopia gives us not only a description of that imaginary land but the actual alphabet used there: More’s friend Peter Giles wrote an addendum to the book that presents the letters and gives an example of the Utopian writing system:

Vtopos ha Boccas peu la chama polta chamaan.

Bargol he maglomi Baccan foma gymno sophaon.

Agrama gymnosophon labarembacha bodamilomin.

Voluala barchin heman la lauoluola dramme pagloni.

This is translated into Latin as

Utopus me dux ex non insula fecit insulam.

Una ego terrarum omnium absque philosophia

Civitatem philosophicam expressi mortalibus

Libenter impartio mea, non gravatim accipio meliora.

And in English this becomes

The commander Utopus made me into an island out of a non-island.

I alone of all nations, without philosophy,

Have portrayed for mortals the philosophical city.

Freely I impart my benefits; not unwillingly I accept whatever is better.

Working backward, this makes it possible to divine the meaning of a few Utopian words: boccas is commander, chama is island, voluala is willingly, and gymnosophaon is philosophy. You couldn’t really talk about much beyond perfect societies, but maybe that’s the point.